By the Numbers: 589

The area, in acres, of oyster reefs targeted for restoration in the Little Choptank and Tred Avon rivers

With its rough shell, gray body and big ecological value, the eastern oyster is one of the most iconic species in the Chesapeake Bay. And for decades, protecting oyster populations has been part of the Chesapeake Bay Program’s work. But it was not until the signing of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement that our partners committed to what is known as a tributary-based restoration strategy, setting a goal to restore oyster reefs in ten Maryland and Virginia rivers by 2025 in order to foster the ecological services these reefs provide.

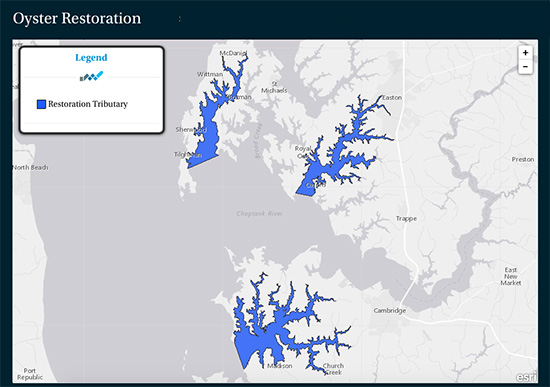

In Maryland, three tributaries—often referred to collectively as the Choptank Complex—have been selected for oyster reef restoration, which will take place where oyster harvest doesn’t occur. While the implementation of restoration treatments in Harris Creek was completed this September, work remains in two other waterways that flow into the Choptank. According to a December update from our Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team, 589 acres of oyster reefs are targeted for restoration in the Little Choptank and Tred Avon rivers. That’s an area bigger than the town of Oxford, Maryland, which is located between the two waterways.

But what does restoring reefs to a tributary entail? The process varies by state and even by waterway. While its overarching steps—from selecting a tributary and setting a target to tracking progress and monitoring oyster health—are often the same, a range of factors can impact the specific course of work. The availability of shell and other hard substrates (which are used to build reefs) and the availability of spat (which are planted on reefs) are of particular concern in a region where both resources are used for other work (including aquaculture and shellfish harvest).

Nevertheless, work is underway in the Little Choptank and Tred Avon. In the Little Choptank, which has a restoration target of 442 acres, 114 acres have been built and 35 have been seeded with spat to date. In the Tred Avon, which has a restoration target of 147 acres, 17 have been built and just over two and a half have been seeded to date. The next progress report from the Maryland Oyster Restoration Interagency Workgroup will be released in spring of 2016, and tributary teams in Virginia will continue their work in the Piankatank, Lafayette and Lynnhaven rivers. The two-year work plan detailing the steps that will be taken to restore reefs in Maryland and Virginia will be released in summer.

Update: On January 13, 2016, the Chesapeake Bay Journal reported that the state of Maryland has instituted a "brief pause" in its construction of oyster reefs in the Tred Avon River. Maryland Department of Natural Resources Secretary Mark J. Belton told the newspaper that the pause will be in place until the state completes an internal review of its oyster management policies, due in July.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories