Blue Crabs

The Bay’s signature crustacean supports important commercial and recreational fisheries. But pollution, habitat loss and harvest pressures threaten blue crab abundance.

Overview

There is nothing more “Chesapeake” than the blue crab. The Bay’s signature crustacean is one of the most recognizable critters in the watershed, supporting valuable commercial and recreational fisheries. However, the blue crab population has fluctuated over time in response to fishing pressure and environmental drivers including pollution and habitat loss. Water quality improvements, seagrass restoration and proper fishery management will help maintain this valuable resource.

Why are blue crabs important?

As both predator and prey, blue crabs are a keystone species in the Chesapeake Bay food web.

Blue crab larvae are part of the Bay’s planktonic community, serving as food for menhaden, oysters and other filter feeders.

Juvenile and adult blue crabs serve as food for fish, birds and even other blue crabs. Striped bass, red drum, catfish and some sharks depend on blue crabs as part of their diet. Soft-shell crabs that have just molted are particularly vulnerable to predators.

Blue crabs are among the top consumers of bottom-dwelling organisms, or benthos. They eat bivalves (i.e., clams, mussels, oysters), smaller crustaceans, freshly dead fish, plant and animal detritus and almost anything else they can find.

Blue crabs feed on marsh periwinkles (snails), helping regulate periwinkle populations. Scientists are concerned that a decline in the Chesapeake Bay blue crab population could negatively affect salt marsh habitat, as periwinkle populations feed on marsh grasses.

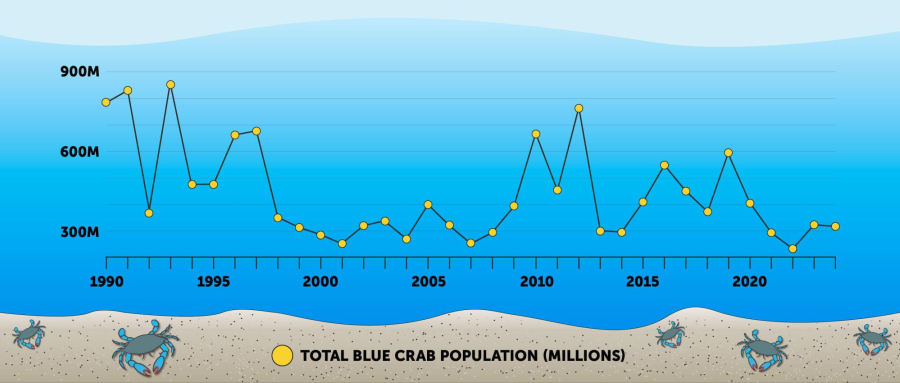

How many blue crabs live in the Chesapeake Bay?

Show image description

The infographic shows an underwater scene with blue crabs resting on the sand. A line chart shows years from 1990 to 2024 on the X-axis and millions of blue crabs on the Y-axis, from 200 million to 900 million. It begins in 1990 just under 800 million, then rises to slightly before dropping all the way to under 400 million in 1992 and jumping to about 850 million the next year. From there, it drops to below 500 million and remains about the same before increasing to above 650 million in 1996. It increases slightly before falling to about 350 million in 1998. From there, it continues dropping slightly to a low of around 250 million in 2001 before rising slightly to over 300 million in 2002 and 2003. It drops back a little, below 300 million, before rising to 400 million in 2005. The next two years show a steady decline to around 250 million, then a gradual rise over three years to nearly 700 million in 2010. 2011 shows a drop to around 450 million and then jump to over 750 million in 2012. Then it drops to 300 million in 2013 and 2014 before growing to about 550 million in 2016 and decreasing to under 400 million in 2018. The last height blue crab population reaches is about 600 million in 2019, before dropping through 2022, where the low is just above 200 million. But the last two data points, in 2023 and 2024, show growth, at above 300 million.

According to data from the Winter Dredge Survey, an estimated 323 million blue crabs lived in the Bay in 2023, which is a 42% increase from 227 in 2022. For most of the last two decades, the total number of blue crabs in the Chesapeake Bay has lingered below the long-term average. Because blue crabs are so important to the region's ecosystem and economy, both Maryland and Virginia monitor the blue crab population through an annual Winter Dredge Survey. The crabs that are collected at each of the survey's 1,500 sampling sites are measured, weighed, sexed and aged, and the data is used to estimate the number of young crabs entering the population, the number of female crabs old enough to spawn and the total number of harvestable crabs in the Bay.

What issues affect blue crabs?

Harvest is a primary source of blue crab mortality in the Chesapeake Bay. But environmental conditions including water quality, weather patterns and habitat also cause the abundance of blue crabs to fluctuate from year to year. Loss of habitat, particularly of underwater grasses and marshes, is a primary concern for the blue crab population in the Bay.

Harvest pressure

More than one-third of the nation’s blue crab catch comes from the Chesapeake Bay. Blue crabs—harvested as hard shell crabs, peeler crabs and soft shell crabs—are the most valuable commercial fishery in the Bay, earning millions of dollars of revenue each year. Blue crabs also support a large recreational fishery in the region.

From the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, there was a dramatic decline in the blue crab population. This decline was thought to be due to “recruitment overfishing,” which occurs when large removals of adults result in fewer juveniles being produced.

According to the 2022 Blue Crab Advisory Report from the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee (CBSAC), 36.3 million pounds of blue crabs were harvested from the Bay and its tributaries during the 2021 crabbing season. Commercial and recreational crabbers harvested 19 percent of the female blue crab population, which is below both the target (28%) and overfishing threshold (37%) of harvest.

Habitat loss

Blue crabs use underwater grass beds and marshes as nurseries, feeding grounds and refuges from predators. A decline in underwater grass abundance—due to warming waters, irregular weather patterns and pollution—has been linked to declines in the blue crab population. Because they are key feeding grounds and predator refuges, underwater grass beds and marshes increase juvenile blue crab survival and growth rates. Research has also shown that denser underwater grass beds can hold more crabs, indicating both the quantity and quality of underwater grass habitat can affect blue crab populations.

Predation

Striped bass, Atlantic croaker, red drum and other predatory fishes feed on juvenile blue crabs. A significant change in abundance of these fish populations could affect the abundance of juvenile blue crabs, and consequently the future of the blue crab population.

How are blue crabs being protected?

Water quality improvements, underwater grass restoration and proper fishery management will help protect blue crab populations and maintain the resource.

Blue crab management

Blue crabs are managed as a single species, using minimum catch size and seasonal harvest limits to meet target levels of fishing pressure. The annual winter dredge survey helps scientists determine where the current blue crab abundance and harvest levels fall in relation to the management targets and thresholds. Under this strategy, the fishing target is set to a level that should allow for sustainable harvest that allows the population to persist at an acceptable level of abundance over time.

The Chesapeake Bay Program developed its first Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Fishery Management Plan in 1989 to promote collaboration among the three jurisdictions that manage commercial crabbing in the watershed: Maryland, Virginia and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission (PRFC). The Bay Program’s Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committeehas continued to provide scientific advice to fisheries managers, publishing a Blue Crab Advisory Report each year.

What you can do to help

To protect blue crabs in the Bay watershed, consider protecting underwater grasses. Boaters should follow posted speed limits and no-wake laws to avoid harming underwater grass beds and steer clear of grasses growing in shallow waters.