In search of a true river monster

The Atlantic sturgeon is slowly recovering in Virginia

About 10 miles downstream from Richmond is a stretch of the James River that quietly bends into a series of dramatic looping oxbows. One afternoon, during the first week of fall, Dr. Matt Balazik piloted his small research boat to the first of these curves. He passed a towering coal plant and forested riverbanks before cutting his motor and preparing his net to try to catch some prehistoric giants that visit these tidal waters.

A bit of wartime history made Balazik’s survey site a prime destination for spawning Atlantic sturgeon, an endangered fish whose massive size—up to 12 feet historically—and propensity for breaching entirely out of the water has begun to lure sightseers. During the Civil War, Union forces carved a canal across one of the oxbows. Today this cut-through is the main channel for the river, known as Dutch Gap. Its deep, gravelly bottom is one of the best sturgeon spawning areas on the river, which is itself a key stronghold for the species.

Balazik, a member of the research faculty at the Virginia Commonwealth University Rice Rivers Center, has been studying sturgeon for roughly 20 years, long enough to get a more accurate understanding of their populations.

“Just a little bit over 15 years ago they thought there was only 300 of these [adult sturgeon], pretty much, in the James,” said Balazik, noting the previous underestimate. “We’ve caught over 160 in one year, and only had one recapture.”

Over the years, Balazik has caught over 900 unique adults in the James, fitting each with unique passive integrated transponders, or PIT tags. The technology is the same used to “chip” pet cats and dogs, though as Balazik pointed out, the practice was developed for tracking fish.

The James River has stations set up to read the tags of passing fish, much like the toll stations on a highway. As he waited several minutes with his net in the water, he pointed out several returning fish that had popped up on scanners.

The tagging also helped dispel a belief that was once widely accepted. Sturgeon are anadromous, meaning they return from life at sea to spawn in freshwater tributaries, like shad and river herring. But until recent years it was believed that sturgeon only spawn in the spring. Just over a decade ago, Balazik published his findings that revealed the existence of the genetically distinct fall sturgeon run in the James. In fact, there are more fall-spawning sturgeon, likely because the spring spawning run was targeted more for harvesting.

As Balazik began hauling in his net, it was only a few moments before his efforts were rewarded with thrashing water and an especially energetic fish.

“Jiminy Cricket, he just hit the net!” Balazik said. “He is feisty.”

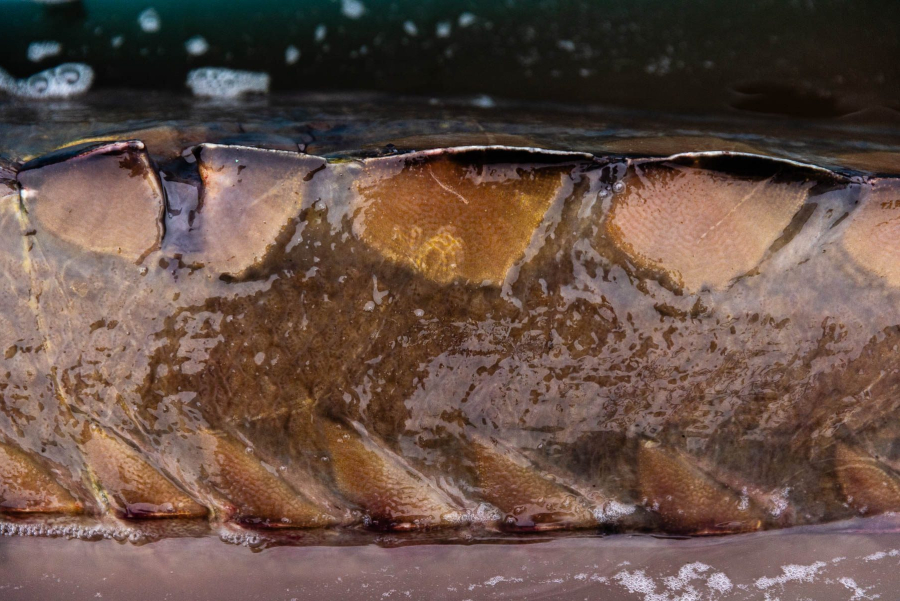

Balazik strained to lift the fish—and then a second—into the boat. Their size and thrashing left Balazik breathing hard after removing the net and dropping them into a tub of circulating water onboard.

The first fish, a male, was a re-capture, first tagged in August of 2017. So all it needed was a quick moment with a tape measure. for its total length to be 1.92 meters, or six feet and three inches from its nose to the tip of its tail.

The second fish, a male measuring just under six feet long, was a first-time capture. So it received a PIT tag, quickly injected under its smooth skin, as well as a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service “spaghetti tag” with a five-digit identification number, poked into the same hole. Balazik also nicked away a small piece of fin, dropping it into a vial of ethanol to serve as a DNA sample.

Balazik estimated that both fish were likely 20 years old or older. That means they probably hatched after a 1998 moratorium halted all commercial harvests of Atlantic sturgeon (following a Virginia ban in the 1970s). They were already several years old when the species was added to the federal endangered species list in 2012. Sturgeon are naturally long-lived but slow to mature, which means their recovery will be gradual.

“Here, a male will mature around 10 [years old], a female around 15,” Balazik said.

Though the threat of harvest is gone, some challenges remain for the Atlantic sturgeon.

“Your big, large container ships will chop them up,” Balazik said, recalling a particularly disappointing case about 10 years ago, when he found a female “pretty much cut in half” on what was probably her first spawning run on the Appomattox River.

Sturgeon have poor vision and hearing—traits that suit its predator-free life of sucking up invertebrates from the bottom of the river, but ones that make them prone to getting sucked into propellers.

“Some of those barges, their prop draft will be 20 feet,” Balazik said. “And if the legal depth is 24 feet, there’s no room for the fish to be in.”

A rising threat may also be coming from predation by blue catfish. This invasive species is also known for growing to great sizes, but it’s actually the small, young catfish that are a problem. When they are several inches long, blue catfish will readily feed on fish eggs and larvae, including sturgeon. One way to counteract this, if the need arises, would be to focus conservation efforts on the survival of young sturgeon.

“If we see that there's a [population] trend down, we may have to think about some more aggressive restoration techniques, maybe some streamside hatchery work,” Balazik said.

Thankfully, so far, his research indicates that the population of sturgeon in the James is increasing.

“The population is still low compared to what it should be, but it's not nearly as bad as we thought,” Balazik said. “And that's really good, because it takes a long time for you to get these adult fish.”

Comments

Very good article. Enjoy these success stories

Atlantic sturgeon is the subject of 2025 "Restore the Wild" art contest.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories