Striped Bass

Also known as rockfish, striped bass are recovering from a severe decline in the 1970s and 80s with the help of fishery management practices and Chesapeake Bay restoration.

Overview

Striped bass—also known as rockfish or stripers—have been one of the most sought-after commercial and recreational fish in the Chesapeake Bay since colonial times. After bouncing back from a severe decline in the 1970s and 1980s, the striped bass population is once again below optimal levels. The 2022 Benchmark Stock Assessment indicated that the population is not currently overfished, but population remain below the management threshold. In addition to fishing pressure, the health of the striped bass population greatly depends on the health of the Bay, which provides critical feeding, spawning and nursery habitats.

Why are striped bass important?

Striped bass are a key predator in the Chesapeake Bay. They play an important role in the food web by controlling prey populations. They also support one of the Bay's most popular commercial and recreational fisheries, generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue in the region annually.

Key predators

Striped bass are one of the top predators in the Chesapeake Bay food web, feeding on both fish and benthic invertebrates. Therefore, large fluctuations in striped bass abundance could cause cascading ecological changes throughout the rest of the food web in the Bay.

Economic value

Striped bass have been one of the most popular commercial and recreational fish species in the Chesapeake Bay for centuries. Their size and fighting ability make them a top sportfish in the Bay, and their delicious taste makes them a favorite item on local restaurant menus.

Striped bass are so acclaimed in the Chesapeake Bay region that the Maryland General Assembly designated it the Maryland state fish in 1965, writing: "Whereas, In the judgment of the members of the General Assembly of Maryland, it is a simple act of justice and of equity that this fine old Maryland fish should be honored by being designated as the official fish of the State of Maryland..."

Why did striped bass numbers decline in the 1970s and 1980s?

The striped bass fishery experienced record-high catches in the early 1970s; in 1973, the commercial fishery landed 14.7 million pounds. But following that year, reported commercial and recreational catches declined steeply. By 1983, the striped bass harvest had fallen to just 1.7 million pounds.

The reasons for the sharp decline in striped bass harvest during the 1970s and 1980s were complex. Scientists primarily attributed it to overfishing, which may have made striped bass more susceptible to pollution and other stresses, including:

- Water temperature fluctuations in spawning grounds.

- Low dissolved oxygen in deeper Bay waters, which eliminated much of the fish's summer habitat.

- Acidity and chemical contaminants in certain spawning areas.

- Poor water quality from runoff from the land and sewage treatment practices.

In response to this downturn, Congress passed the Atlantic Striped Bass Conservation Act in 1984. Maryland and Delaware imposed fishing moratoria on striped bass from 1985 through 1989, and Virginia imposed a one-year moratorium in 1989.

The Chesapeake Bay fishery reopened in 1990, after three-year average recruitment levels exceeded an established threshold value. The striped bass population continued to recover thanks to adaptive, coast-wide management and suitable environmental conditions. In 1995, the population was officially declared restored. In the years since, catches varied from year to year, mostly remaining within a healthy range. But now, the population is in a state of concern, with biomass below the management threshold and the exploitation rate above the threshold, indicating that the population is overfished and overfishing is occurring.

How many striped bass are in the Chesapeake Bay?

Show image description

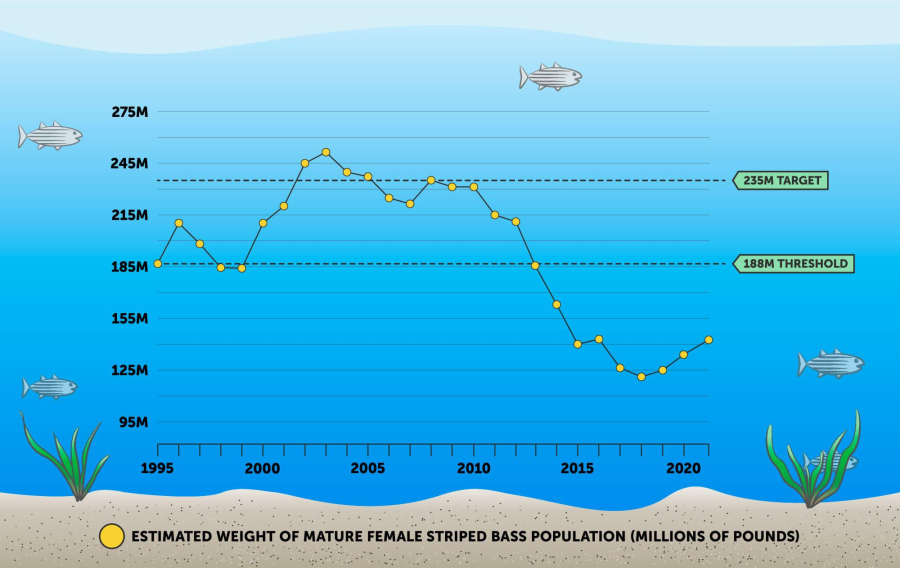

The infographic shows an underwater scene with striped bass and green vegetation. A line chart illustrates the estimated weight of the Chesapeake Bay's mature female striped bass population, measured in millions of pounds, from 1995 through 2021. The line chart includes one horizontal line to indicate a target of 235 million pounds and one horizontal line to indicate a threshold of 188 million pounds. In 1995, the estimated weight of the Bay's mature female striped bass population measures about 185 million pounds. In 2003, this figure peaks at above 245 million pounds before beginning a downward trend. In 2018, this figure reaches a low of less than 125 million pounds. But from 2018 onward, this figure slowly increases, surpassing 140 million pounds in 2021.

In 2021, the female spawning stock biomass was estimated at 64,805 metric tons (143 million pounds) according to the According to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. This is below the updated spawning stock biomass threshold of 85,457 metric tons (188 million pounds), and below the updated target of 106,820 metric tons (235 million pounds). The stock is still above the mid-late 1980s moratorium levels.

To survey young striped bass, scientists use seine nets to sample in known striped bass spawning areas. The average number of juveniles (less than one year old) caught in each seine haul is used to calculate the juvenile striped bass index. These young-of-year fish will grow to a fishable size in three to four years.

The 2021 young-of-year index is 3.2 in Maryland waters, which is slightly higher than last year, but still well below the long-term average of 11.4. Striped bass reproductive success varies from year to year, but the below average index is a concern that biologists will continue to study. In Virginia waters, the index is 6.30, which is similar to the historic average of 7.77 and represents the ninth consecutive year of average or above-average recruitment in Virginia waters. This suggests that abundance of juvenile striped bass in Virginia has been relatively stable.

What issues currently threaten striped bass?

In addition to overfishing, a number of environmental and biological factors threaten the striped bass population in the Chesapeake Bay. These include habitat loss, pollution, hypoxia (low oxygen), changes in prey abundance and disease. Climate-driven changes in temperature and precipitation patterns may further impact striped bass’ ability to bounce back from declines. When multiple stressors are present at the same time, such as warmer waters with low oxygen, striped bass are even more vulnerable to disease and mortality. Scientists are currently working to better understand the conditions that lead to a good or bad year for striped bass.

Overfishing

Overfishing occurs when fish are removed from a population at a rate that cannot be naturally replenished, resulting in a smaller population. Continued overfishing over a period of time can result in the total removal of the species from the area. According to the 2018 Benchmark Stock Assessment, the fishing mortality rate of striped bass in 2017 was estimated at 0.31, which is above the threshold of 0.24. This indicates that overfishing is occurring. In an attempt to reduce the fishing mortality and end overfishing, managers implemented more restrictive fishing regulations coast-wide in 2020.

Habitat loss

The Chesapeake Bay is the primary spawning and nursery ground for 70 to 90 percent of the Atlantic striped bass stock. Therefore, loss of high-quality habitats is a major concern for striped bass spawning and for the survival of young striped bass. Excess nutrients that enter the water through urban, suburban and agricultural runoff can make conditions unlivable while threatening structured habitat such as submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), which are important nursery areas for juvenile striped bass. Additionally, hardened shorelines can negatively affect shallow-water habitats that striped bass need. Nearshore environments where the fish spend time avoiding predators and feeding on prey are also threatened by development and pollution.

Prey abundance

Scientists and resource managers want to make sure that there is enough prey to adequately support predator populations in the Chesapeake Bay, including striped bass. Striped bass diets consist primarily of forage fishes such as bay anchovy and menhaden, as well as benthic invertebrates including polychaetes and shrimps. Having enough of key forage species supports healthy growth rates for striped bass.

Disease

Scientists are concerned about the high prevalence of a disease called mycobacteriosis among Chesapeake Bay striped bass. Since the late 1990s, researchers have documented an increased occurrence of external lesions associated with mycobacteriosis in striped bass. In response, Maryland striped bass disease monitoring data were used to investigate the potential connection between mycobacteriosis and environmental conditions such as water quality.

Findings of the study suggest that the proportion of fish that test positive for the disease is correlated with water quality, and that the prevalence of mycobacteriosis seems to increase as nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment pollution increases. Therefore, efforts to reduce nutrient and sediment loads play a critical role in striped bass recovery in the Chesapeake Bay.

How are striped bass managed?

Management of the striped bass population in the Chesapeake Bay and along the Atlantic Coast is coordinated by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). The Commission brings together partners from eight commercial jurisdictions and 16 recreational jurisdictions to set management regulations based on the best available science.

ASMFC set coast-wide fishery management plan (FMP), from Maine to North Carolina, for striped bass. In turn, the Chesapeake Bay Program has worked since 1989 to follow ASMFC annual guidelines and requirements, including:

- Developing regulations to allocate and control safe harvest levels.

- Determining stock assessment and research needs.

- Examining the effects of environmental conditions, such as habitats and water quality, on striped bass stocks.

How you can help

To protect striped bass, make sure to follow proper fishing regulations. You can also help keep striped bass and other aquatic animals healthy by preventing pollution from entering local waterways:

Install a green roof, rain garden or rain barrel to capture and absorb rainfall.

Use porous surfaces like gravel or pavers in place of asphalt or concrete.

Redirect home downspouts onto grass or gravel rather than paved driveways or sidewalks.

If possible, install living shorelines to stabilize waterfront property without damaging seagrass beds and other nearshore habitats.