Capturing sea ducks on the Chesapeake Bay

Take a midnight trip on the icy Bay to learn how scientists brave sleep deprivation and frigid weather to monitor sea ducks.

“You’re going to want to take those off for this.” Alicia points to my gloves.

Exposing my hands to the cold – the kind of bitter cold that strikes only in the middle of winter, in the middle of night, in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay – did not seem like something I’d ever “want” to do. Why did I volunteer for this again?

But Alicia Berlin, leader of the Atlantic Seaduck Project, has given me the job of untangling something called a "mist net." The net’s delicate fabric is quick to catch on fabric as we stretch it forty or so feet across the Chesapeake Bay. So I reluctantly shed the gloves, exposing my bare hands to winter’s icy chill.

Alicia and her team hope to capture surf scoters and black scoters in the mist net, and then arm them with GPS-like trackers that allow researchers to monitor the ducks’ migration patterns and feeding habits.

Since sea ducks only visit the Chesapeake Bay in winter, and since they are most active in the pre-dawn hours, Alicia’s team works in the cold darkness to assemble the mist net and trap these vacationing birds.

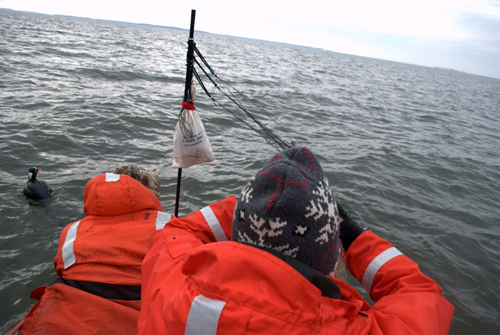

I quickly realize that unraveling the mist net is the easy job. The other volunteer I’m working with is leaning over the edge of the raft, his bare hands in the water; his headlamp the only source of light to illuminate his task.

He’s huffing and puffing and shivering as he pulls our raft along the anchor line, waiting for me to untangle the net above him before we can move forward. I stand nearly on top of him, praying I don't trip and fall overboard into the black, bone-chilling water just a foot below us. It’s so cold I can smell it.

Minutes later, we’re staring at our end product: what looks like a large volleyball net floating in the middle of the water, surrounded by two dozen decoys (plastic fake ducks) bobbling on the frigid waves. The darkness is turning gray, so we rush to our second location and set ourselves on repeat.

Once we finish our setup, there’s nothing left to do but wait. I try to force myself to stay alert – to listen for ducks calling, to search the horizon for flying silhouettes coming towards our decoys – but I can't. The frosty weather is numbing every part of my body, even though I’m wearing a ridiculous-looking "survival suit," a garment reminiscent of Randy's snow suit in A Christmas Story.

I’m not the only one who’s falling asleep sitting up. I met Alicia and her team on the Eastern Shore at 1 a.m., giving me just three hours of sleep. The more consistent volunteers are completely exhausted, pulling all-nighters followed by eight-hour work days. This collective sleep deprivation leads to an interestingly honest team dynamic and contributes to a plethora of freak accidents. (Alicia somehow drove our boat directly into a mist net just minutes after we had set it up.)

One can only hope that our lack of sleep will pays off, but not a single duck has flown into the mist nets all week. Perhaps tonight will make up for team’s previous disappointments.

Apparently, mist netting isn’t the most effective technique to capture sea ducks. According to Alicia, night lighting is far more successful. A team goes out on the water in the middle of the night, preferably in rainy weather, and shines flood lights on the water to locate ducks. Volunteers then capture the unsuspecting ducks in nets.

Captured ducks are kept in cages on the boat until morning. Then they’re transported to Patuxent Research Refuge in Laurel, Maryland, where a surgeon implants the tracking devices in the ducks. (Alicia assures me the ducks can't feel the device.) The next evening, lucky volunteers set the sea ducks free on the Chesapeake Bay.

(Image courtesy Andrew Reding/Flickr)

The number of sea ducks wintering on the Chesapeake Bay has decreased in recent years due to food availability and the effects of climate change. Many sea ducks rely on bay grasses that only grow at certain depths and are affected by algae blooms and high temperatures.

I’m awakened at sunrise by honks and quacks. My raft mates and I scope out the skies in different directions, identifying packs of ducks that will hopefully visit our mist net. My eyes follow pair after pair flying toward the net; but at the last minute, each one goes over or around it. Perhaps these birds are smarter than we give them credit for.

The larger boat that’s watching the second net has similar bad luck. That team decides to sneak up on a pack and drive the birds in the general direction of our nets. After a mess of quacking and fluttering, the ducks head not for the net, but directly toward our raft!

We chase the ducks around the Bay until 10 or 11 that morning, but not a single sea duck gets caught in the nets we worked so hard to set up. 'Tis the unpredictable nature of wildlife biology, the team says. Everything is a constant experiment: from the team's capture technique to the location of the nets to the weather. Failure is simply part of the learning process. Alicia is confident that tomorrow will bring better luck, and that night lighting next week will guarantee results.

We disassemble the mist net and head toward the shore, just in time to beat the growing waves that signal an approaching rain storm.

I've never been happier to bask under an automobile's heat vents.

Comments

You must have been tired....I hunted sea ducks for many years.....never once did any of them quack!

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories