Decoy carvers show Chesapeake Bay birds at Waterfowl Festival

Hand-carved decoys reflect the cultural heritage of their creators and the landscapes behind the birds.

Millions of ducks, geese and other waterfowl visit the Chesapeake Bay each year, finding food and habitat in marshes across the watershed. Hunters have long gone after these birds as a source of food, using wooden or plastic decoys to attract them to their blinds. But in recent decades, what were once tools of the hunting trade have become works of art, and modern decoys showcase the carving styles of the artists behind the birds.

“[Decoys] started out as a means of putting food on the table, of attracting live birds,” said Kristin Sullivan, a Ph.D. candidate who studies the heritage behind decoy carving at the University of Maryland. But this soon changed: “By the 1950s, decoys started to become mass-produced, so hunters could get fairly cheap plastic or wooden birds and didn’t have to carve them out themselves.” This, paired with a burgeoning collector’s market created by hunting parties who kept hand-carved decoys as souvenirs, turned decoys into decorative, collectible items.

Now, tourists are a big customer for decoy carvers. So, too, are people who have “some sort of connection to hunting, or some… sort of connection to the landscape from which the bird came,” Sullivan said. Indeed, decoys carved in the Bay region are often evocative of the estuary. “A decoy is going to reflect the landscape,” said Sullivan.

But decoys also reflect the personality of the carver. We interviewed five carvers at the Waterfowl Festival in Easton, Md., to find out how they started carving, what makes their work unique and how the Bay has informed their birds. You can find our questions and their answers below.

Robert Clements, Clements Creations and Woodworking, Smithsburg, Md.

What drew you to decoy carving?

This show did. In about 1987, I came down here for the first time, and decided that once I retired from the Secret Service, this was going to be my job. So way back when, in 1987, is when it all started. I was cutting through one of the buildings, and in a little hallway, there was a gentleman… who was hand-chopping decoys. And I thought that was the neatest thing in the world, that someone could do that. So I’m all self-taught. After I retired, I got a bunch of reference books and I sat out in my workshop and that’s all I did until I felt that [my work] was at a point where I was comfortable with it.

Describe your carving style.

What I like to do is what they call contemporary antiques. It’s just a new bird they try to make old. [Another carver] told me to come up with your own style, don’t copy anybody else, do what you want to do. And that’s exactly what I decided to do.

How has the Chesapeake Bay inspired or informed your work?

I grew up in Takoma Park, and we had relatives around the Bay. I wasn’t a typical Bay guy, but being in the state of Maryland and [experiencing] all the history related to the Bay—you can just get caught up in it.

What role do waterfowlers play in conservation?

The whole hunting type person—you’d be surprised how those people are more in tune with the environment than the techno guys with their iPads and iPods. I think the hunting guys—the old guys especially—can give you a perspective of exactly how they did things in the beginning and how they do things now. It’s probably a 180 degree turn.

What is your favorite bird to carve?

It’d have to be a wood duck. I hate painting them, but they have so many colors in them the bird just pops. It’s a pain to do, but it’s probably the prettiest bird out there.

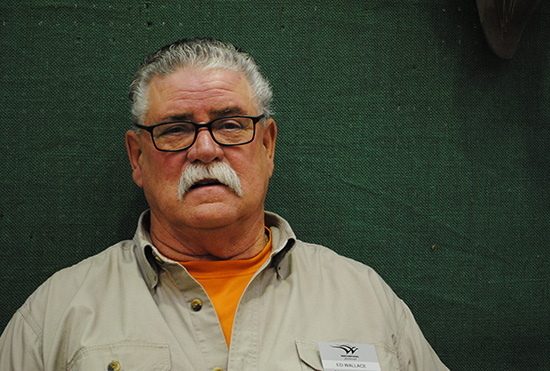

Ed Wallace, Wildfowl Carvings by Ed Wallace, Galena, Md.

What drew you to decoy carving?

I’ve been carving for about 30 years. We used to visit the Waterfowl Festival all the time, and I was down here and I said to myself one time, I think I can do that.

Describe your carving style.

Well, it’s my style. I have never had a lesson, and I don’t give lessons, because I want to do birds my way. I don’t want to do a bird like somebody else, and I don’t want somebody else to do a bird like mine.

How has the Chesapeake Bay inspired or informed your work?

At one time, I was a commercial hunter. I took hunting parties [out] and grew up on the Bay. It’s just bred into you.

What role do waterfowlers play in conservation?

More than a lot of people think. You know, they preserve what they have. And if they don’t, there’s not going to be any [more birds].

What is your favorite bird to carve?

A mallard drake. Why? I don’t know. I don’t like to do wood ducks; I don’t know anybody that does. I did one a couple of months ago, and that’s probably the last one I do. I don’t mind the carving. But I don’t care what you do, you can’t make one look natural.

Gilmore B. Wagoner, Quality Working Decoys by Gilmore B. Wagoner, Havre de Grace, Md.

What drew you to decoy carving?

A necessity. When I first started hunting in the early sixties, we couldn’t afford to buy decoys, so we made them. And the first ones we made were made from two by fours and two by sixes. Kind of looked like something a little kid would make, but they worked. We were making blue bills and canvasbacks, and we made some mallards, but they weren’t that good. Back in the old days, all you had to do was paint a tin can solid black and it would work. You could decoy a duck with just a painted one-gallon can. Now, they’re manufacturing decoys for the hunter, not for the ducks. The prettier a decoy is, it draws the hunter to them. It doesn’t, per se, draw the duck to the decoy.

Describe your carving style.

My carving style today is Upper Chesapeake Bay. I worked for [Havre de Grace decoy carver] Madison Mitchell for approximately seven years. While I was working for him, I worked for the federal government at Aberdeen Proving Ground, where I tested military equipment. The person you go to if you live in Havre de Grace and you want to learn how to make decoys is Madison Mitchell. I don’t think there’s a decoy maker in Havre de Grace that did not work for him.

How has the Chesapeake Bay inspired or informed your work?

I’ve always lived in Havre de Grace. I’ve never lived beyond three blocks from the water. When I was a kid, back in the early fifties, our whole summer was spent around that water, swimming, fishing, crabbing or doing whatever kids seven, eight, nine, 10 years old do. It’s a heritage thing with me, just like the rest of the guys here on the Eastern Shore. They grow up on some of the islands around here; they were brought up fishing, crabbing and eeling. We just followed the path of our forefathers and our grandfathers and our fathers. It’s in our blood. I’ll probably never leave Havre de Grace or leave the water.

What role do waterfowlers play in conservation?

I’ve always been associated with Delta Waterfowl, Ducks Unlimited and even this organization here, the Waterfowl Festival. I’ve always given decoys so they can raise money. Of course, they transfer the money into their conservation efforts. I donate the material or the products, so they can raise the money and do the [conservation] work.

What is your favorite bird to carve?

I have two. Widgeon, a.k.a. bald pates, and pintails. Canvasbacks are okay, but there’s just so many of them around. I tend to lean toward the more colorful ducks: mallards, pintails and widgeon. That’s generally what I like to carve, something more colorful.

Jeannie Vincenti, Vincenti Decoys, Havre de Grace, Md.

What drew you to decoy carving?

My husband, [Patrick Vincenti], is a carver. I work with him on a daily basis, and I run our store in Havre de Grace. My husband was drawn to [carving] because he was a hunter, and as a hunter, he had a need to make his own decoys. As he started making them, people wanted them, so he left his full-time job in 1986 to be a full-time carver.

Describe his carving style.

It’s definitely a Maryland-style bird. But more specifically, it’s an Upper Bay working decoy.

How has the Chesapeake Bay inspired or informed his work?

Living next to this estuary—which is probably one of the best in the world—the duck hunting here was outstanding. It still is. So I would have to say, the availability of the ducks made the desire to make the decoys and hunt, and as you hunted all those years and you made the decoys, you develop a tremendous respect for that Bay and its richness.

What role do waterfowlers play in conservation?

Just like deer hunters or anything else, you have to keep the numbers of birds in check, because there’s not enough food. And as we infringe upon their space, there’s less food for them. So by following the rules and the guidelines of waterfowling, you’re doing it in a fair and right way, and you’re keeping the numbers in check, just like you would for deer or any other animal.

What is your favorite bird that you and your husband sell in your store?

My husband’s would be the canvasback; mine would have to be the black duck. I like the way he paints it, and it just has a look that I like. But the canvasback is the bird that is most desirable, and [Pat] has a strong fondness for canvasbacks.

Charles Jobes, Charles Jobes Decoys, Havre de Grace, Md.

What drew you to decoy carving?

My dad has made decoys for 63 years. We all made decoys as kids; I’ve got two brothers, younger brother Joey, older brother Bobby. My dad worked for Madison Mitchell in Havre de Grace, Madison Mitchell is my godfather. So we more or less worked for my dad, all of us coming up. As the years went on, we always worked on the water crabbing, fishing and making decoys. And I’ve made decoys for a living for probably 35 years. We all make decoys for a living now.

Describe your carving style.

The carving style is a Chesapeake Bay decoy—an Upper Chesapeake Bay decoy. Where we live, the carving style of the decoy [features] an up-curved tail [and] regular, slick paint. It’s a regular gunning decoy paint style and carving style, made out of white pine and cedar and basswood.

How has the Chesapeake Bay inspired or informed your work?

When we were kids, we body booted on the Susquehanna Flats, [standing in the water, surrounded by decoys]. It’s an area that years ago, in the twenties and thirties and even before that, was home to hundreds of thousands of canvasbacks. Everybody would come to the Flats to kill canvasbacks, black heads and redheads. The Chesapeake Bay is an estuary where all the ducks and geese come in the wintertime, and that was the first place that they stopped, coming down. Then they would disperse through the whole Bay. We grew up on that water.

What role do waterfowlers play in conservation?

When they started the [U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Federal] Duck Stamp in 1937, when Ding Darling made the first Duck Stamp, that was the first conservation stamp. All that money goes to waterfowl. If you didn’t have waterfowlers that hunt, there would be no money to go to the wetlands that Ducks Unlimited restored in North Dakota, South Dakota, the boreal forest. There wouldn’t be anything.

What is your favorite bird to carve?

Canvasback. Drake canvasback. They’re probably the easiest duck to make, but they’re the king of ducks. They’re just so pristine, and they’re a neat duck. They’re the king of the Chesapeake.

Comments

I have a miniature duck with what looks like carl Bl 1970 do you know anything about him. Can't read the last name

Who is M Walters? I have three signed M Walters shore birds circa 1980 but can't find any information of the man or women. Can you help? Thanks.

Mar.23 2025 At flea mkt today bought two decoys signed Gilmore B Wagoner Havre de Grace, Md. 1988. bought for 10$ ea. beautiful condition didn’t know what he had.

Have a duck decoy/carving signed by George Dumas, Gruen Street Cheasapeake, VA on hang tag

I have 2 miniature hand carved ducks that my dad left me. He worked at the Edgewood Arsenal for many years. One duck is signed by Frank D and the rest is now not very legible other than Edgewood Md. The other says. To Bob. A nice guy. Frank. My dad treated these like they were made of gold. When he passed he made sure I got them. I have pics and would love to know anything

Hey Barbara, it appears Jim and Joan Seibert once owned Ducks, Etc., in Cape May County. Here's an article we found about them: https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/27/nyregion/antiques-the-art-of-the-decoy-carver.html

I have a duck carved in '88 signed by., it looks like, J. Seibert. Can you give me any info on this. Thank you

Hi Carol,

We're not familiar with that artist, but you could try contacting the Havre De Grace Duck Decoy Museum (https://decoymuseum.com/) or the Waterfowl Festival (https://www.waterfowlfestival.org/).

Good luck!

I have a duck decoy that was carved by I believe first initial is D, with last name being Yenkes and it is dated 1973.

Do you have any info you could share about the carver? I could send photos of decoy. I believe this decoy is for display only.

Thanks

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories