Fewer incentives, boost in commodity prices mean decline in on-farm forest buffer restoration

Streamside trees are critical to the Bay, but planting rates continue to drop.

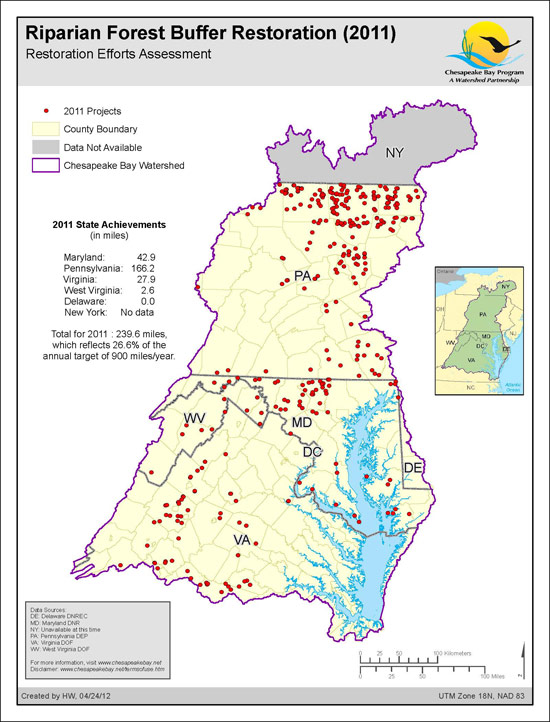

The restoration of forested areas along creeks and streams in the Chesapeake Bay watershed continues to decline.

Called riparian forest buffers, these streamside shrubs and trees are critical to environmental restoration. Forest buffers stabilize shorelines, remove pollutants from contaminated runoff and shade streams for the brook trout and other fish species that thrive in cooler temperatures and the cleanest waters.

While more than 7,000 miles of forest buffers have been planted across the watershed since 1996, this planting rate has experienced a sharp decline. Between 2003 and 2006, Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania planted an average of 756 miles of forest buffer each year. But in 2011, the entire watershed planted just 240 miles—less than half its former average.

Farmers and agricultural landowners have been the watershed’s driving force behind forest buffer plantings, using the conservation practice to catch and filter nutrients and sediment washing off their land. But a rise in commodity prices has made it more profitable for some farmers to keep their stream buffers planted not with trees, but with crops. This, combined with an increase in funding available for other conservation practices, has meant fewer forest buffers planted each year.

But financial incentives and farmer outreach can keep agricultural landowners planting.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), for instance, has partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and others to implement conservation practices on Pennsylvania farms. Working to put the state’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) funds to use, CBF provides farmers across the Commonwealth with technical assistance and financial incentives to plant forest buffers, often on the marginal pastureland that is no longer grazed or the less-than-ideal hayland that is rarely cut for hay.

The CBF Buffer-Bonus Program has encouraged Amish and Mennonite farmers to couple CREP-funded forest buffers with other conservation practices, said Dave Wise, Pennsylvania Watershed Restoration Manager with CBF. The reason, according to Wise? “Financial incentives … make it attractive for farmers to enroll.”

Image courtesy Chesapeake Bay Foundation

For each acre of forest buffer planted, CBF will provide Buffer-Bonus Program participants with up to $4,000 in the form of a “best management practice voucher” to fund conservation work. This comes in addition to CREP cost-share incentives, which fund forest buffer planting, post-planting care and annual rental fees that run from $40 to $350 per acre.

While Wise has witnessed what he called a “natural decline” in a program that has been available for more than a decade, he believes cost-share incentives can keep planting rates up, acting as “the spoonful of sugar" that encourages farmers to conserve in a state with the highest forest buffer planting rates in the watershed.

“There are few counties [in the Commonwealth] where buffer enrollments continue to be strong, and almost without exception, those are counties that have the Buffer-Bonus Program,” Wise said.

In 2007, the six watershed states committed to restoring forest buffers at a rate of 900 miles per year. This rate was incorporated into the Chesapeake Bay Executive Order, which calls for 14,400 miles of forest buffer to be restored by 2025. The Chesapeake Forest Restoration Strategy, now out in draft form, outlines the importance of forests and forest buffers and the actions needed to restore them.

Comments

Excellent presentation of a disturbing subject. Hurray to CBF for its incentive program

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories