Five signs of resilience in Chesapeake Bay health

While more work remains, estuary shows signs of progress

Since our formation in 1983, the Chesapeake Bay Program has been leading the effort to reduce pollution and restore ecosystem health across the Chesapeake Bay region. Whether through the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, signed in 2014, or the Bay’s ‘pollution diet’—i.e., the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL)—our partners have continued to work collaboratively toward our shared goal of a healthy Bay.

With decades-worth of environmental data, our scientists are able to study how the health of the nation’s largest estuary is changing over time. Below, learn about a few of the ways the Bay and its rivers have been showing signs of resilience.

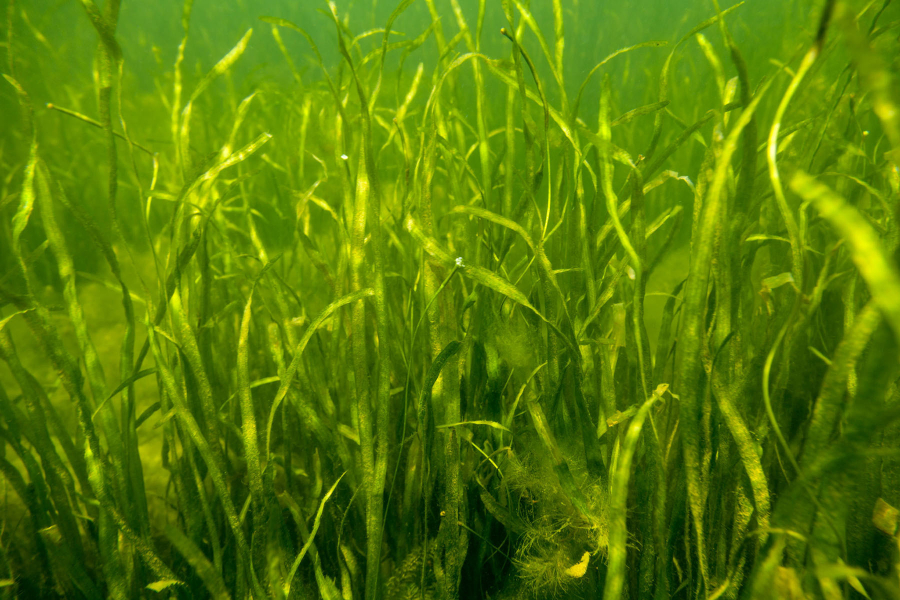

Record acreage of underwater grasses

Underwater grasses, also called submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV, grow in the shallow waters of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. They provide food and habitat to wildlife, add oxygen to the water and trap and absorb pollution. Because of their sensitivity to pollution, the abundance of underwater grasses can serve as an indicator of restoration progress.

Between 2014 and 2015, more than 92,000 acres of underwater grasses were observed in the Chesapeake Bay. An increase of 21 percent from the previous year, it marked the highest amount ever recorded in the nearly 30 years the Virginia Institute of Marine Science has conducted their aerial survey. Part of this increase was due to the expansion of widgeon grass—often referred to as a “boom or bust” species because its abundance can rise and fall from year to year—but other species like wild celery and eelgrass also saw a recovery.

The blue crab is one of the most iconic species in the Chesapeake Bay, supporting commercial and recreational fisheries in the region. But vulnerability to pollution, loss of habitat and harvest pressure have led their abundance to fluctuate over time; in 2014, adult female blue crabs were considered depleted.

Joint management between Maryland, Virginia and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission has helped maintain the Bay’s blue crab stock at sustainable levels. At the start of last year’s crabbing season, there were an estimated 194 million adult female blue crabs in the Bay—a 92 percent increase from the previous year. And according to the 2016 Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Advisory Report, the blue crab stock was not depleted and overfishing was not occurring.

Higher levels of dissolved oxygen

Just like humans, crabs, fish and other underwater animals that live in the Bay need oxygen to survive. Dissolved oxygen is a measurement of how much oxygen is present in the water; as dissolved oxygen levels decrease, it becomes more difficult for animals to get the oxygen they need.

As reported in the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s most recent Chesapeake Bay report card, dissolved oxygen levels in many regions of the Bay were frequently in “good condition” (scores of 60 percent or higher) in 2015, and no regions were below “moderately good” levels. Additionally, 2016 marked the second consecutive year that there were no measured anoxic areas—or areas with no dissolved oxygen—in the main portion of the Bay.

Improvements in bottom-dwelling invertebrates

Organisms that live at the bottom of the Bay and its rivers and streams are known as “benthos.” Benthic communities are made up of worms, clams, oysters, shrimp-like crustaceans and other underwater invertebrates, and they provide food for crabs and bottom-feeding fish.

In 2015, almost two-thirds of the bottom habitat in the tidal Bay was home to a healthy community of benthic organisms, an increase from 59 percent in 2014. In addition, the area of degraded and severely degraded habitat—or areas that are home to more pollution-tolerant species, fewer species overall, fewer large organisms deep in the sediment and a lower total mass of organisms—was the lowest it has been since 1996. Scientists attributed this improvement to increases in dissolved oxygen.

Declines in nutrient and sediment pollution

While some nutrients and sediment are a natural part of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem, too much can be harmful to fish, shellfish and other underwater life. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus can fuel the growth of algae blooms, which can lead to low-oxygen dead zones that suffocate marine life. Sediment can cloud the water, preventing sunlight from reaching underwater plants and smothering bottom-dwelling species.

According to data from the Bay Program and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment loads to the Bay were below the long-term average in 2015. Additionally, since 1985, long-term trends in nitrogen pollution have improved at six of the nine monitoring stations located along the biggest rivers that feed into the Bay, including at stations in the region’s four largest rivers: the Susquehanna, Potomac, James and Rappahannock.

Want to learn more about our work toward achieving the goals of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement? Visit ChesapeakeProgress.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories