It takes a partnership to save an estuary

For more than three decades, the Chesapeake Bay Program partnership has been leading the restoration effort

As the story goes, the cleanup of the Chesapeake Bay began with a boat trip. In 1973, after hearing reports of the estuary’s ailing health, Sen. Charles “Mac” Mathias, R-MD, set out on a “fact-finding tour”: a five-day trip traversing the Maryland portion of the Bay and hearing firsthand the experiences of 150 watermen, scientists, farmers, businesses and other area residents.

What he heard and saw troubled him. Harvests of oysters, crabs and fish were declining; watermen, fishermen and others who depended on the seafood industry were going out of business. Underwater grasses were disappearing, and with them the waterfowl dependent on grass beds for food. The water was clouded with sewage and other pollutants, and industrial processing plants were leaking heavy metals, such as chromium, into local waterways.

In 1975, at Mathias’ urging, Congress funded a $27 million, five-year study of the Bay. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), then just five years old, was charged with coordinating the investigation into the estuary’s failing health.

When the results were published in the early 1980s, they painted a grim picture: declines in underwater grasses, young oysters and spawning fish; decreases in the dissolved oxygen needed to support underwater life; and high concentrations of toxic contaminants. Perhaps most importantly, the results pointed overwhelmingly at nutrients—mainly nitrogen and phosphorus—as the main culprits of the Bay’s poor water quality.

Today, excess nutrients are well-known to be the main problem plaguing Bay health. But as Walter Boynton remembers, “When we and others started to find these strong system responses to nitrogen, it was controversial.”

Boynton, an estuarine ecologist at Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, co-authored one of the first scientific papers that established the role that nutrients play in the Bay’s degradation. “In the 1960s, the idea was that you could not pollute estuaries,” he said. “You just didn’t need to worry about them, because they were flushed by the tides. Then it became clear that, well, you can pollute estuaries, and one of the big issues was the nutrient issue.”

As Boynton often reiterates, he was just one of many researchers at the time looking into the issue. With so many scientists coming to the same conclusions, the volume of findings was impossible to ignore: Nutrients from wastewater, urban and suburban runoff, farm fields and air pollution were overfertilizing the Bay, resulting in massive algae blooms, disappearing underwater grass beds, degraded habitats and low-oxygen dead zones.

A leader for the Bay cleanup

As efforts to understand the cause of the Bay’s poor health were under way, another question was arising: Who would be in charge of fixing it? With an estuary that crosses state lines and a watershed that encompasses 64,000 square miles, coordination and oversight of the restoration effort required a collaborative, multifaceted approach.

“When they began that effort to study the Chesapeake, some legislators from Maryland and Virginia realized that there was no interstate body to act on the findings and recommendations of the watershed study,” Ann Swanson said. Since 1988, Swanson has served as director of the Chesapeake Bay Commission, which was established in 1980 by Maryland and Virginia to assist the states in managing the Bay. Today, the Bay Commission includes members from Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania—who joined in 1985—and advises each state on matters of Baywide concern.

In 1983, the Bay Commission sponsored a conference at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. More than 700 attendees gathered to watch as representatives from Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, the EPA, and the Chesapeake Bay Commission convened to sign the first Chesapeake Bay Agreement committed to restoring the Bay and establishing what is known as the Chesapeake Bay Program.

Led by the Chesapeake Executive Council, which today comprises the governors of the six watershed states; the D.C. mayor; the chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission; and the EPA administrator, who represents the federal government—the Chesapeake Bay Program is the regional partnership that leads the multi-state effort to protect and restore the Chesapeake Bay. It functions as a vast network of partners from federal and state agencies, local governments, nonprofit organizations and academic institutions working on goal teams, advisory committees and workgroups toward the common goal of a healthy Chesapeake Bay.

A series of agreements

When that original Chesapeake Bay Agreement was signed, it became the first in a series of several that have guided the Bay Program’s work over the years. Written agreements have become a hallmark of the Bay Program—as has a rigorous monitoring program to track the progress of partners’ efforts. Established in 1984, the Baywide effort known as the Chesapeake Bay Monitoring Program measures an array of characteristics in the Bay and its tributaries, allowing Bay Program partners to detect changes over time and improve their understanding of the estuary ecosystem.

“We had many meetings, arguing about what to measure, how often to measure it,” said Boynton, who was part of the group that created the monitoring program. “Eventually, we settled on what I still view as a pretty comprehensive monitoring program.”

One of the key aspects of that monitoring structure has been measuring the amount of nutrients, sediment and water flowing into the Bay from its major rivers, an effort coordinated by the U.S. Geological Survey through their River Input Monitoring Program.

Other monitoring that measures the effects of nutrients on the ecosystem includes typical water quality variables like chlorophyll a and dissolved oxygen, as well as underwater grasses and living resources like fish, crabs and oysters. Through the Chesapeake Bay Monitoring Program, states were able to establish consistent standards and assessment procedures for monitoring a water body that spanned state lines—an achievement that was previously unheard of.

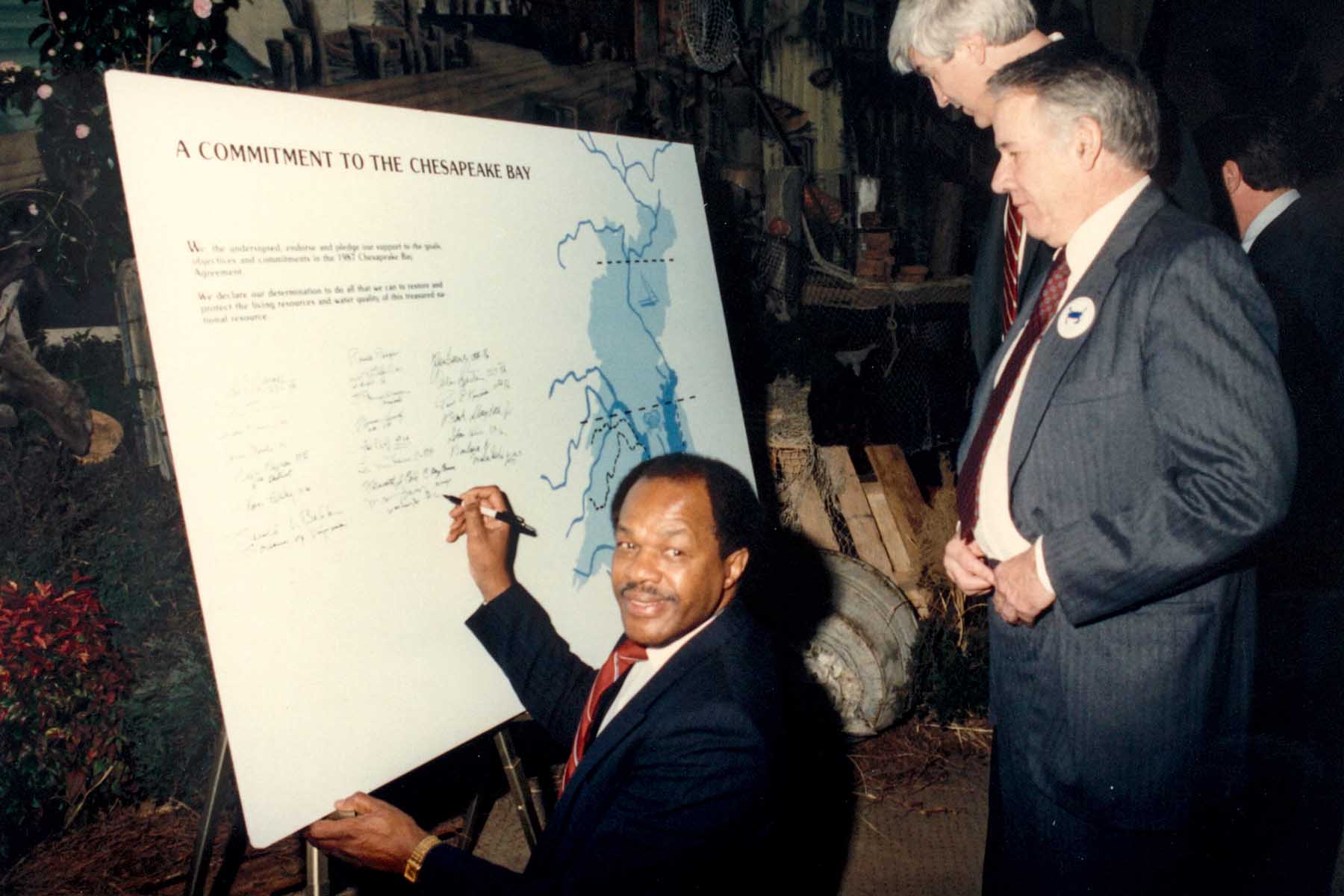

With the Bay Program established, new partnerships formed and the monitoring system in place, the rapidly growing restoration effort was ready to begin setting goals. In contrast to the simple, one-page original agreement, the subsequent 1987 Chesapeake Bay Agreement expanded in scope to include goals for public access, population growth, land development and living resources. The work took a collaborative, ecosystem-centric approach still used by the Bay Program: State and local partners agree to an outcome, then individually decide on their preferred method for reaching those restoration goals.

For some of the goals, progress was somewhat straightforward, simply because not much of the work had been spoken for yet. “There was a newness to the challenge, and the enormity of the task allowed you to pick and choose what you worked on. And, you were able to choose some of the easier courses of action, because the selection on the playing field was broader,” Swanson said. “That being said, every time we did something difficult and gutsy, it took energy, and it took passion and it took tenacity.”

Setting goals, deadlines

As part of the 1987 agreement, the Bay Program also set its first numeric goal: decrease the amount of nutrients entering the Bay by 40 percent by 2000. At that time, agreeing to numeric goals with specific deadlines was unprecedented. Today, it’s characteristic of how the Bay Program operates.

This type of specific, quantifiable goal-setting was particularly important to Bill Matuszeski, who served as director of the Bay Program from 1991 to 2001. “It’s really important to have goals that are understandable by the public and readily measurable,” Matuszeski said. “What’s important to people is, how are the crabs doing compared to the last 30 years? How are the grasses doing, and where they’re not doing well, why?”

By the late 1990s, the deadline for meeting the goals of the 1987 agreement was approaching, and Bay Program partners began to look back on their progress toward achieving what they set out to do. What they saw was a mix: Some goals were on track, others weren’t.

“We felt that it was time to come up with a new set of goals, a new set of concrete measures, and what we had learned a lot from previous years that would allow us to do that,” Matuszeski said. The resulting discussions culminated in another written agreement, known as Chesapeake 2000. This agreement established 102 commitments to reduce pollution, restore habitats, protect living resources and engage the public in Bay restoration.

The early 2000s also marked another milestone in the history of the Bay Program: It was the first time that the Bay’s headwater states—Delaware, New York and West Virginia—officially joined the Bay Program’s restoration efforts, with each state committing to work toward the agreement’s water quality goals. For Matuszeski, their inclusion was a natural step. Although 1987 amendments to the Clean Water Act meant that the EPA has a statutory responsibility to participate in the Bay Program, states generally have the lead in guiding the restoration effort, and their collaboration and cooperation is key to keeping up momentum.

With a wide array of partners and a vast, varied watershed, the Chesapeake Bay restoration effort faces challenges similar to those of other environmental programs, but often at a much larger scale. Finding a balance among the interests of federal, state and local partners while facing the complexities of a large ecosystem home to millions of residents and significant economic interests can sometimes make progress feel out of reach.

As the deadline for meeting Chesapeake 2000’s goals approached, it was clear that success would be varied. Significant restoration gains were seen in conserving land, planting riparian forest buffers and reopening streams to fish passage, but limited progress was made in areas like oyster abundance and reducing nutrient pollution.

The Chesapeake Bay TMDL

Around the same time, new directives were arising to manage the Bay Program’s restoration efforts, although some were far different from the voluntary agreements that had guided its past work. In 2009, President Obama signed Executive Order 13508, declaring the Chesapeake Bay a “national treasure” and renewing the federal government’s efforts to restore the watershed. And, in 2010, at the urging of the Chesapeake Executive Council, the EPA established the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL)—the largest and most complex of its kind—which sets limits for the amount of nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment allowed to enter the Bay.

Still, the voluntary nature by which partners engage in the restoration effort is a cornerstone of the Bay Program, and in 2014, a new agreement was signed. Called the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, it aligned current and emerging Bay restoration work, incorporating the requirements of Executive Order 13508 and the Chesapeake Bay TMDL while adding goals to support sustainable fisheries, protect vital habitats, boost environmental literacy and increase climate resiliency, among others. Continuing its tradition of accountability and transparency, the Bay Program offers up-to-date, accessible data on progress toward meeting these goals through its oversight website, ChesapeakeProgress.

Throughout its existence, the innovative structure and science used by the Bay Program have inspired similar efforts across the nation and world. Its trademark practice of setting measurable goals and deadlines is now a common method used by restoration programs across the country. The suite of environmental models used to simulate the Bay ecosystem are among the most sophisticated, studied and respected in the world. And the partnership served as a model for the National Estuary Program, which has targeted 28 estuaries throughout the United States for restoration and protection.

“As I say to people, if we can clean up Chesapeake Bay, nobody else in the world has an excuse,” Matuszeski said. “It takes a lot of effort, it takes a lot of money, it takes a lot of political will, but it can be done.”

While plenty of work remains, signs of recovery have begun to appear. Water clarity has improved in recent years, after several decades of slow decline. During late summer, dissolved oxygen can be found in the Bay’s deep waters—a previously rare occurrence. Underwater grass abundance was estimated to be more than 97,000 acres in 2016, much more than the 38,000 acres observed in 1984. Experts are cautiously optimistic, but decades of investment, persistence and enthusiasm appear to be having a positive effect on Bay health.

“We are witnessing improvements in our health and restoration indicators even during periods of normal or near normal rainfall and rivers flows, not just following periods of drought,” said Nick DiPasquale, former director of the Chesapeake Bay Program. “This is evidence that our efforts to reduce nutrients and sediment pollution discharges are working.

“We are at a tipping point where the ecosystem functions are in a state of recovery and are mutually supportive, creating a positive feedback loop that will reestablish the balance and resilience of the system,” DiPasquale said. “It is critical that we continue and accelerate our efforts so we can achieve our water quality standards and restore the living resources of this watershed.”

This article originally appeared in the Bay Journal.

Comments

Excellent article on the history, development and current process of trying to restore the Chesapeake Bay by cooperating States to establishing the Chesapeake Program. 2024 measurements (TMDL) of the Bay's health must be significant. We have seen the 2020 Pandemic cause many practices & policies to change. Such as how more people are working from home on their lap tops. Getting more people to walk, bike and exersize in redevelopment master planning. Changes in using Commercial properties from office use to residential use; from forested land & stream to open spaces for sports and recreation; from Stormwater Management Plan Managers trying to better address forecasted increases in water velocity from more frequent storms and heavier downpours flowing from impervious surfaces into tributaries down to rivers and the Chesapeake Bay. Has the Chesapeake Program leadership looked into the unintended destructive impacts on streams, tributaries and rivers due to the MDE MS4 Stream Restoration's Scope of Work requirements to achieve TMDL, that was funded & completed; that the Chesapeake Program will rigorously monitor and fund to restore improvements to the biodiversity of each degraded MS4 stream restoration project?

So important to remember where we have come from and the conplicated and comprehensive work that has been completed. So much progress so far that just has to continue! Thanks for reminding us!

Great article! Very, very useful for those of us who became involved in bay conservation recently and have been trying to assemble enough information on the history of restoration efforts to see the whole picture. Thank you!

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories