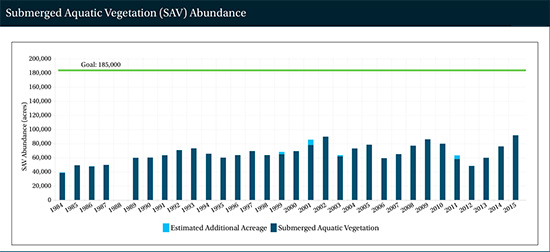

Monitoring finds more than 91,000 acres of underwater grasses in Chesapeake Bay

The 2015 acreage exceeds the 2017 restoration target two years early

Between 2014 and 2015, underwater grass abundance in the Chesapeake Bay rose 21 percent, bringing underwater grasses in the nation’s largest estuary to the highest amount ever recorded by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science aerial survey and surpassing the Chesapeake Bay Program’s 2017 restoration target two years ahead of schedule.

Aerial imagery collected between May and November of 2015 revealed a total of 91,621 acres of underwater grasses across the region. Experts attribute this spike to the recovery of wild celery and other species in the fresher waters of the upper Bay, the continued expansion of widgeon grass in the moderately salty waters of the mid-Bay and a modest recovery of eelgrass in the very salty waters of the lower Bay.

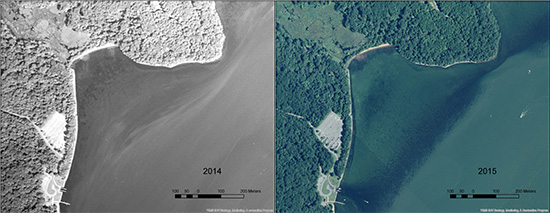

In the Elk River, for instance, grass beds that had been decimated after Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee hit the region in 2011 recovered in 2015. While the beds were not as dense as those seen the season before the storms pushed water-clouding nutrient and sediment pollution into the northeastern Maryland waterway, they were larger and more diverse than previously observed and surpassed the river’s 1,648-acre restoration target. Wild celery, whose seed pods and roots offer food to migrating waterfowl, was the dominant species detected.

Because freshwater species like wild celery are resilient, continued improvements in water quality are expected to support the continued expansion of these grasses. In spite of this good news, experts advise cautious optimism about the state of underwater grasses overall: because widgeon grass is known as a “boom and bust” species whose abundance can rise and fall from year to year, the widgeon-dominant spike we have seen is not guaranteed to persist in future seasons.

“While much of the grass that accounts for the 2015 expansion was widgeon grass—a species that is often described as a boom or bust plant—I think we can take heart in the fact that it boomed last summer—marking three consecutive years of growth,” said Maryland Department of Natural Resources Biologist and Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Workgroup Chair Brooke Landry in a media release. “Be it freshwater wild celery or mid-Bay widgeon grass, submerged aquatic vegetation would not expand so rapidly and into areas where it hasn’t been mapped before if water quality wasn’t improving. This report shows that we are making strides on Bay restoration and truly impacting the amount of nutrient and sediment pollution entering our waterways. As we continue to provide conditions necessary for our natural resources to thrive, their resilience will increase and they’ll have a much better chance of persisting through major weather events or other challenges.”

Underwater grass beds are critical to the Bay ecosystem. They offer food to small invertebrates and migratory waterfowl; shelter young fish and blue crabs; and keep our waters clear and healthy by absorbing excess nutrients, trapping suspended sediment and slowing shoreline erosion. For these reasons, the Bay Program has committed to achieving and sustaining 185,000 acres of underwater grasses in the Bay, with a target of 130,000 acres by 2025.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories