Nature's dazzling parade of lights

While humans delight one another with electrical lights that twinkle on trees and dazzle on banisters, nature brings her own glowing displays au naturale in the form of "living lights": bioluminescence.

Bioluminescence, or light emitted from a living creature, does not give off heat. A molecule of oxygen, the protein luciferin and the enzyme luciferase combine, exciting molecules which can then give off light.

Diverse and complex, nature's spectacular light shows can be found in almost every form.

In heaven and earth: Angel’s glow

The “Battle of Shiloh” is an 1888 chromolithograph by illustrator There de Thulstrup showing the Civil War battle known for the appearance of angel’s glow.

The “Battle of Shiloh” is an 1888 chromolithograph by illustrator There de Thulstrup showing the Civil War battle known for the appearance of angel’s glow.

Over the course of two days in the beginning of April 1862 near Shiloh, Tennessee, one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War occurred. When the battle was over and the smoke cleared, more than 16,000 wounded men covered the ground as rain poured down. The wounded were too many for the field hospitals. Men with open wounds lay in muddy water and waited to die in the rain.

Yet some, the soldiers and doctors believed, were touched by the angels. As the critically wounded languished in the fields, cold and dying, their injuries began to glow with a soft blue light. The men that glowed overwhelmingly lived out the wait for doctors.

When they were finally taken below the medical tent, the men did not contract infections. They healed much faster than their non-luminous brothers-in-arms. Seeing it as a kiss of heaven’s protection, soldiers referred to the light as the “angel’s glow.”

The instrument of the angels turned out to be Photorhabdus luminescens, found right in the soil beneath our feet.

The ground we walk on every day is not a dead thing, but rather a complex biome filled with life. In the Tennessee fields and here in the Chesapeake watershed are nematodes, a type of worm that lives in the soil. Nematodes hunt and feast on insects in the soil, spitting up toxin-producing bacteria—in this case Photorhabdus luminescens—into the insects.

The bacteria immobilizees the insect and breaks it down. Then the nematode ingests it once more. As a byproduct of this process, the bacteria glows. Photorhabdus luminescens also has antibacterial properties, ensuring it has no competition from other bacteria for its insect meal. It is this antibacterial property which saved the soldiers’ lives.

Why do we not see the angel's glow phenomenon more often? Human bodies are normally too warm for Photorhabdus luminescens to survive, but conditions in the field were miserable. The exhausted and wounded soldiers lying in the muddy water soon had hypothermia set in. This owered their body temperatures and created an easy invitation for the life in the soils. The bacteria colonized their wounds, preventing infection, and the soldiers glowed.

In sand and wave: Dinoflagellates

A bloom likely caused by high concentrations of the bioluminescent dinoflagellate Alexandrium monilatum appears in a long exposure made the evening of Sept. 23, 2012 near York Point in Seaford, Va. (Photo courtesy Wolfgang Vogelbein/Virginia Institute of Marine Science)

Every so often in the Chesapeake, people walking the shores at night are treated to a green or blue glow in the water. This often happens in summer, with August being a common month. Tiny plankton, called dinoflagellates, contain bioluminescent pigment that reacts with oxygen to create the glow.

Dinoflagellates are one-celled aquatic organisms, taxonomically debated. Botanists call them algae; zoologists call them protozoan.

Either way they are tiny creatures, with roughly 750,000 dinoflagellates per cubic feet of affected water. Each individual is small, at about one five hundredth of an inch, but their bioluminescent capabilities far outshine their size. When gathered together, they put on a magnificent light show.Ceratium is said to put out a twinkling light; Noctiluca plankton is described as having a greenish glow.

In Virginia's summer of 2015, Alexandrium monilatum lit up the night in Virginia’s York, James, Lafayette and Elizabeth rivers.

According to Scott Phillips in Peary, Va., “It was magical. You could see stingrays swimming six feet down. A pod of dolphins swam by, leaving a 30-foot trail of light. Crabs clicking their claws even lit up the water. Never seen anything like it.”

If you find yourself in view of such a spectacle, be cautious. Blooms of dinoflagellates may be beautiful, but they can also be dangerous. Some species produce toxins and can cause widespread kills in aquatic life.

Waves aren't the only place that you’ll see evidence of the dinoflagellates. Those familiar with the shore will tell you that sand crabs, the pod-shaped crawlers that like to dig into the sand at the edge of the waves, will also bioluminesce.

While it isn’t well documented, the likely cause of lit-up sand crabs is an overabundance of dinoflagellates from gorging on blooms. Sand crabs are filter feeders, so as they filter the water, dinoflagellates can stay in their bodies and lend them their glow.

In the air: St. Elmo’s Fire

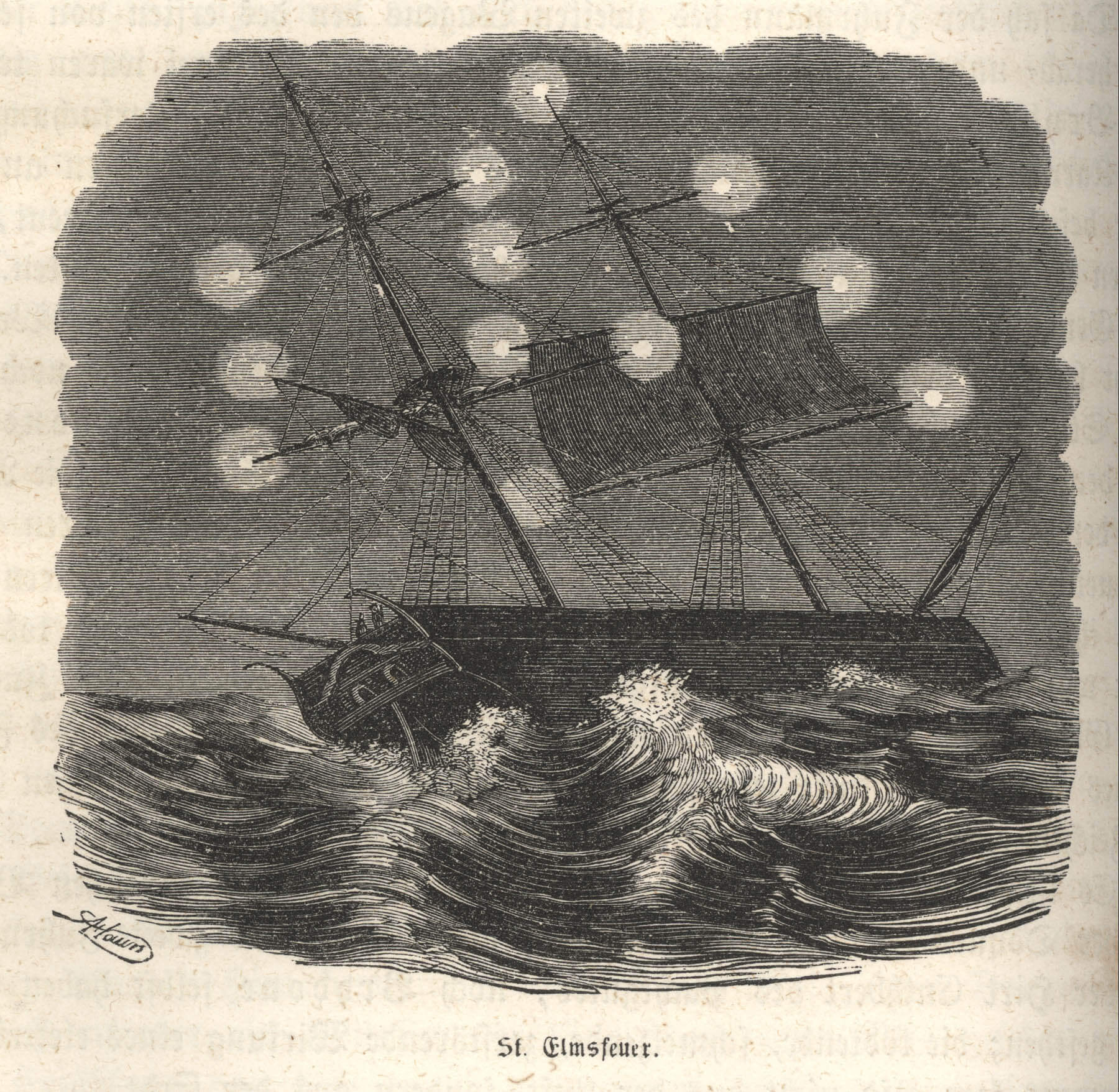

The St. Elmo’s Fire phenomenon is depicted illuminating a ship in the book Naturwunder Im Reiche der Luft by Dr. W.F.M. Zimmerman, circa 1860.

The St. Elmo’s Fire phenomenon is depicted illuminating a ship in the book Naturwunder Im Reiche der Luft by Dr. W.F.M. Zimmerman, circa 1860.

Climbing the mast of a ship is a dangerous undertaking for a sailor. Falling to the deck below or being struck by lightning strikes from above are serious threats. Sailors turned to the skies for help to get home. To help lessen the danger they took on a saint as their patron. He was said to have continued fearlessly preaching even after lightning struck directly next to him. This was St. Erasmus, which was shortened to St. Elmo.

After violent storms would pitch a ship at sea, sailors would sometimes see purple fire shooting from the tips of the masts and spars as the clouds cleared. The fire did not burn the ship, and the sailors thought it to be a sign from their patron. The phenomenon came to be known as St. Elmo’s fire.

While sailor stories are often dismissed as “whale tales,” nature can be stranger than fiction. Thunderstorms electrically charge the atmosphere, causing electrons to move further away from protons as the air becomes ionized. The mast acts as a lightning rod, and the energy is released in the form of a plasma discharge that glows blue or purple. The pointed tips of masts and spars offer an area of lower voltage and a path of least resistance, so light appears to shoot out of the ends.

As technology has advanced, so has the way we encounter nature in all its force. Rather than the masts of sailing ships, St. Elmo’s fire is now most often encountered on the tips of plane wings. In rare instances on land, this phenomenon has even been reported sparking across the tips of cattle horns.

In the sea: Jellies

A pink comb jelly, Beroe ovate, from the Rhode River in Anne Arundel County, Md., is seen on Oct. 10, 2014. (Photo courtesy Robert Aguilar/Smithsonian Environmental Research Center)

A pink comb jelly, Beroe ovate, from the Rhode River in Anne Arundel County, Md., is seen on Oct. 10, 2014. (Photo courtesy Robert Aguilar/Smithsonian Environmental Research Center)

Swimming in the ocean or the Bay comes with joys and risks, and one of those risks happens to be the jellyfish. Made mostly of water, jellyfish are intriguing with their mostly transparent and gelatinous bodies. They are difficult to see while recreating in the water, and they can lead to painful stings for the unwary.

If you are someone who holds a negative opinion of jellyfish, try visiting the water at night for a different perspective on these Bay dwellers: some of them glow.

Moon jellyfish are one of the Bay’s largest jellyfish. While intimidating during the day, it can be a sense of wonder at night to see a moon jelly’s blueish light.

For those that still can’t stomach the tentacles, you may be more partial to the comb jelly. This jelly ball has no tentacles and is only four inches in size. In the Chesapeake, they flash a green light when they are disturbed. Float at night in a dinghy or kayak, enjoy the peace and be treated to a light show as green glowing comb jellies roll in your wake.

In the forest: Foxfire

Luminescent Panellus is seen in the daytime in Randolph County, W.Va. (Photo courtesy Randy Bodkins/CC BY-NC 4.0)

Luminescent Panellus is seen in the daytime in Randolph County, W.Va. (Photo courtesy Randy Bodkins/CC BY-NC 4.0)

The woods are lovely, deep and not always as dark as portrayed. On rotting logs in mossy abodes, you may be treated to the otherworldly gleam of foxfire: a bioluminescent fungus found in forests throughout the world.

The mushrooms we see growing on tree trunks and across the ground are not individuals, but merely tiny parts of a vast fungal network. Mushrooms grow through mycelium, a threadlike substance that weaves its way down through logs and land to form colonies hundreds or thousands of times larger than what we can see.

The glow itself is awe-inspiring. The reasons behind it are perhaps more so: foxfire's bioluminescent glow may have contributed to its long-term survival. The glow is produced as the fungus breaks down wood, which is its food source. Passing insects are thought to be drawn in by the green hue, and these visiting insects can then spread the foxfire spores to new food sources. The strategy must work well, for foxfire has been around for centuries: Aristotle referred to it as “a cold fire burning on logs.”

In water, on land or in the air, nature has many ways to dazzle with light.

Have you seen bioluminescent light displays? Tell us about it in the comments.

Comments

I found bioluminescence in my soil in A.A.C.O. that I had been feeding compost, compost teas, and organic inputs. Happened in late July/Early August two years in a row. Looked almost like mycelia?? It was under the top layer, I discovered it pulling weeds at night. I held it in my hand both years and saw the light dissipate. It appeared to be fiberous, clinging to small debris, sticks, under leaves.

Just saw about a hundred comb jellies in Marley Creek and while watching I saw something else. There was a weird flash of light in the water which was hovering/swimming around. It looked like a tiny fish that kept lighting up. It was in the sun and in the shadows making the light. It was not a reflection. I have no idea what it was but I have never seen anything like it coming from the Bay.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories