Virginia fish collection preserves and archives local species

The Virginia Institute of Marine Science is home to the only collection of Chesapeake Bay fish.

When the start of a new school year drives students into the library, it’s not always a given that they are looking at books. In fact, one marine research center in Virginia is home to a library filled with fish.

The Nunnally Ichthyology Collection at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) contains more than 100,000 freshwater, estuarine and marine fish specimens for use in research and education. The collection is curated by Eric J. Hilton, an associate professor of marine science who has spent a great deal of his life around collections of fish and reptiles. But this one, he says, is unique: after taking on “orphaned” specimens from two other laboratories, VIMS has become the only institution to actively maintain a collection of Chesapeake Bay and mid-Atlantic fish.

The preservation process starts with the euthanization of the fish. Then, the specimen is soaked in a formalin bath to prevent tissue decay and breakdown.

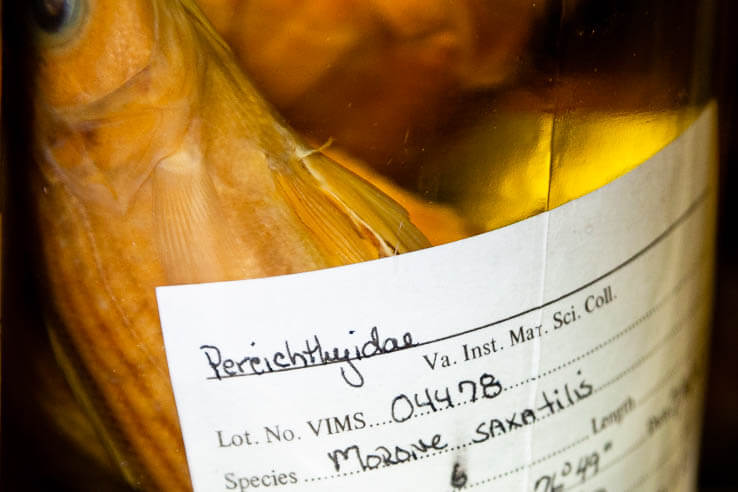

Once the specimen is completely soaked (larger fish take quite a bit more time to preserve than smaller fish), the formalin is flushed from the body and the specimen is placed in a jar that contains a 70 percent ethanol solution.

Oftentimes, multiple specimens of a single species are collected and catalogued. Because there is always variation in nature, researchers prefer to compare and contrast multiple fish of the same species to gain a well-rounded perspective of what the fish and the area they live in are like. “Looking at [only] one individual from a [single] locality will not give you a good view of that locality,” Hilton said.

Each jar is given its own catalogue number that will follow the specimen far into the future. “With that [catalogue] number comes species identification, and all of the attributes of when and where that fish was caught and how it was caught,” Hilton said. “[The number] is entered into a catalogue that is accessible to people throughout the world.”

VIMS also collects a limited amount of skeletal remains in order to conduct skeletal analyses of certain species. “We hope that someday, people can come to the Chesapeake Bay and ask, ‘What was here in 2013?’ and get to see those species and specimens,” Hilton said. If the collection is properly cared for, its fish could be kept for well over 200 years. In fact, some natural resource libraries in Europe are more than 400 years old.

Because its specimens have been collected over decades, the library contains evidence of changes in the Bay. The southern flounder, for instance, is typically found off the coast of North Carolina and other southern waters. Historically, adult southern flounders have made their way to the southernmost portions of the Bay only during hot summer months when the water is warm. But in recent years, researchers have found young southern flounder in the Bay and have added them to the VIMS collection. This new addition indicates a northward shift of southern flounder spawning grounds, likely due to warming waters and climate change.

The fish collection also stores vital information about the introduction and spread of invasive species like the northern snakehead or blue catfish across the state of Virginia and the Bay watershed. Hilton explains: “We have snakeheads from different drainages, so we can track their invasion. We have some of the first juvenile blue cats, and can get a sense of where and when the invasions start.”

Despite the recent addition of new species, the collection’s primary purpose is to track fish that are native to the Bay, like the Atlantic sturgeon or the lined seahorse.

VIMS plans to continue their fish collection efforts for the foreseeable future. After all, as science and technology advance, researchers can conduct new tests on older specimens and learn things about the species or its environment that they might not have known before. “If you stop collecting, you limit what you are able to do,” Hilton said.

To view more photos, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program Flickr page.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories