Record rainfall causes wild seasonal fluctuations for dissolved oxygen in the Bay

Heavy river flows and prolonged warm weather cause dead zone to last well into October

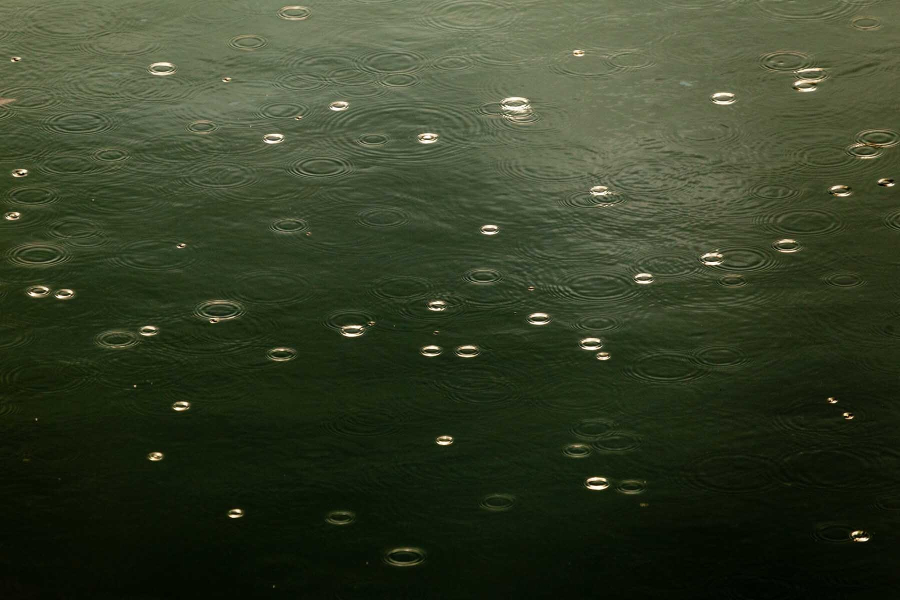

The Chesapeake Bay watershed has sure seen a lot of rain in 2018. From Pennsylvania having its wettest July and August on record to Maryland dealing with its second-wettest July of all time, the Bay has received an unusually high amount of fresh water so far this year. This summer’s historic rainfall led many to wonder how the extra freshwater would affect the Bay’s dead zone.

A dead zone is an area of little to no dissolved oxygen that forms when nutrient-fueled algae blooms die and decompose. The decomposition process removes oxygen from surrounding waters faster than it can be replenished, and the resulting low-oxygen conditions can suffocate marine life such as blue crabs, oysters and fish.

The Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) monitor the Bay’s dead zone each summer and reported similar dissolved oxygen conditions this year. Overall, they consider the 2018 dead zone to be of average size, but the seasonal patterns varied wildly.

DNR monitoring cruises in the early summer showed an above-average dead zone in the deepest waters of the mainstem of the Bay, most likely attributed to double the amount of rainfall normally received in May that caused higher-than-average springtime river flows into the Bay.

Wind speed and direction, as well as temperature, also play a large role in the severity of the dead zone. In July, wind effects from strong storms caused an unusual mixing of the Bay’s surface water with the lower-oxygen waters at the bottom, reducing the dead zone to almost zero. However, the dead zone began growing again only two weeks later, and by September it had developed into a near-record size for that time of year.

The mainstem Bay continued to see low-oxygen conditions into October, a situation most likely caused by the increased freshwater from the heavy rainfall. A higher concentration of freshwater into the Bay strengthens stratification, which is when different water masses form layers that act as barriers to the mixing of the air-filled surface waters and the lower-oxygen deeper waters. The increased stratification, prolonged warm weather into the fall months and more nutrients flowing into the Bay from the high river flows were most likely responsible for the lingering dead zone this year.

Experts believe that climate change is also playing a role in the size and duration of the Bay’s dead zone. Late spring is now behaving like early summer, causing low-oxygen conditions to begin earlier and last longer. Warmer waters hold less oxygen, which can make dead zones easier to form.

The fluctuations in the size of the dead zone this year show us two things: in the long-term, the dead zone has been decreasing, meaning that the pollution reduction strategies put into place by the Chesapeake Bay Program and its partners are working; but in the short-term, weather events such as prolonged warm weather and heavy rainfall can drastically cause dissolved oxygen levels to vary.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories