Saving the Eastern Shore’s marshes from destructive, invasive nutria

A team of scientists and trappers is working to eradicate nutria from the Chesapeake Bay by 2015.

As the sun rises, bald eagles swoop from tree to ground; Canada geese honk happily in a nearby field; and a crew of scientists, boaters and trappers begin a day’s work at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Cambridge, Maryland. The mission? To keep the marshes that fringe the shoreline along this part of the Chesapeake Bay from disappearing.

Although wetland degradation can be attributed to a variety of factors, the field crew at Blackwater is focusing their efforts on one cause they believe can be easily controlled: an invasive rodent called nutria. Native to South America, nutria were introduced to the United States in the early 20th century for their fur, which was thought to be valuable at the time. These 20-pound animals with the build of a beaver and the tail of muskrat may seem harmless, but their effect on marshes across the United States has been devastating.

An overindulgent diet of wetland plants, a lack of natural predators and ridiculously high reproduction rates are characteristics that have led nutria to be labeled as an “invasive species.” Simply put, this means they aren’t originally from here, and they harm the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem.

The problem with nutria

Nutria eat 25 percent of their body weight in marsh plants per day. Let’s put that into perspective: if you’re a 120-pound woman, you’d have to eat 30 pounds of plants each day to eat like a nutria. And since marsh plants don’t weigh all that much, you’d find yourself eating a lot of vegetation.

To make matters worse, nutria tear up the roots of marsh plants when they eat, making it impossible for new plants to grow. As a result, large areas of marshland erode away to open water.

“One property owner on Island Pond had a 300-acre marsh property. Now there’s about 30 acres left,” describes Stephen Kendrot, who works on the Nutria Eradication Project for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services (APHIS).

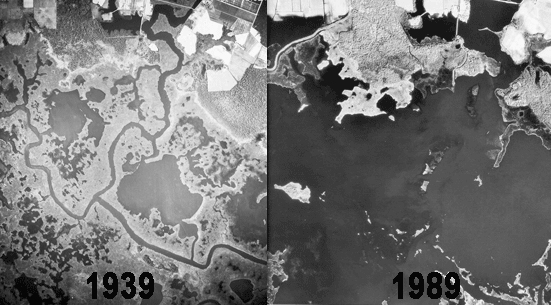

Aerial photographs of Blackwater depict a similar scenario. The refuge has lost 50 percent of its wetlands since nutria were introduced in the 1940s. The photos below depict Blackwater in 1939 (left) and 1989 (right.)

Certainly, this loss is a tragedy for Eastern Shore landowners. And while residents may be disappointed that they can’t look out at a beautiful marsh view or help their children find frogs in their backyard wetland, loss of marshland also results in irreversible ecological consequences.

Marsh plants are incredibly beneficial to the environment because they:

- Filter out pollutants before they flow into the Chesapeake Bay.

- Trap water-clouding sediment, which blocks sunlight from reaching bay grasses.

- Provide food and habitat for countless fish, shellfish, birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians.

Why blame nutria for marshland loss? After all, they are cute, cuddly balls of fur!

In the early 1990s, U.S. Fish and Wildlife staff fenced off random quarter-acre plots in Blackwater’s marsh, excluding nutria but allowing other animals to enter. After several growing seasons, the marsh plants inside the enclosure began to grow, while the vegetation outside the fencing declined. This finding proved that nutria was the direct cause of marsh loss.

Like most rodents, nutria are prolific breeders. This means that those areas with just one or two nutria won’t stay that way for long. Female nutria are fertile as young as six months old, and they can become pregnant again just 24 hours after giving birth. (Essentially, a lifetime of being pregnant.)

“Sometimes we miss a couple animals and they might find each other and start a new population,” explains Kendrot.

A nutria eradication (and wetland restoration) partnership

As the nutria problem grew serious, federal and state agencies, universities and private organizations partnered to form the Nutria Eradication Project. The project team is made up of academically trained biologists and Eastern Shore natives who have been trapping nutria since they were kids.

Although nutria have been eradicated from Blackwater since the project took off in 2002, there are still substantial populations in other, less densely populated areas. These are the spots the Nutria Eradication Project is now targeting.

Today, Kendrot and I tag along with the field team to survey for nutria on the Wicomico River, an area where residents have reported nutria.

Mario Eusi, who has been trapping nutria for years, drives our boat down the Wicomico River and turns into a narrow inlet. This area is privately owned, but the landowners have granted the team permission to access their property. This type of support is critical to the project’s success.

“About half the nutria we find are on private property,” Kendrot explains. “And almost all the property on the Wicomico is privately owned.”

Consequently, the team dedicates lots of time to public outreach. Kendrot and other team members make phone calls and sit down at kitchen tables across Wicomico and Dorchester counties to explain the harmful effects of nutria. The team must assure landowners that if they grant access to their land, they are preventing their property from disappearing. From this perspective, the federally funded Nutria Eradication Project is actually a public service to waterfront landowners – the team does their best to prevent residents’ marshland from sinking into the Chesapeake Bay.

“A nute was here.”

Today we are tracking nutria, which means looking for signs such as scat, paw prints, chewed plants, flattened grass beds – anything to prove “a nutria was here.” A good tracker must have both a keen knowledge of what nutria signs look like and the sharp senses to catch them, regardless of weather conditions or the speed of the boat cruising down the river. The team also tracks nutria through other methods, including dogs, radio collars and hidden video cameras.

Finding the “nute” is the bigger half of the battle. “Trapping is the easy part,” the field team assures me. Team members must first find signs of nutria before they can decide where to set traps in the spring. I admit: I’m relieved I won’t have to see any nutria in traps today.

The tide is rising, so we have to be quick; soon, the water will wash away paw prints and make it difficult to identify nesting areas. Eusi points out the difference between nutria and muskrat scat. His eye for detail and ingrained awareness of the great outdoors makes him an excellent tracker.

Suddenly, we find a nesting site: an area of flattened grasses that looks like someone has been sitting in the marsh. The signs multiply, and soon the team is out of the boat, bushwhacking through twelve-foot high cattails. I try to catch up, but my foot gets stuck in the mud, and soon I am up to my hips in wetland!

As we continue through the marsh, we find one of the most conclusive signs of an active nutria population: a 10-foot-wide “eat-out,” or an open area where nutria have eaten all of the grasses and their roots. These bare, muddy areas, stripped of all vegetation, eventually erode away into open water.

When we spot a larger “eat-out” not a few steps away, it occurs to me that the two areas will likely merge into one giant mud flat. The cattails I just bushwhacked and the mud I sank into will soon disappear forever into the Wicomico River.

Trapping – but not for fur

Since we have successfully tracked nutria on the Wicomico today, the team can now think about how to trap the animals.

When a nutria is trapped, it drowns quickly. Team members record the age and sex of each nutria to determine if it is newly born or if it was missed during the previous round of trapping. One way to estimate a nutria’s age is to weigh its eyeballs, because the lenses grow at a fixed rate throughout its life.

Dead nutria have another benefit: carcasses left in the wild provide food for bald eagles, turtles and other wildlife.

Saving the land – and our money

While the term “eradication” may conjure up images of ruthless killers, the field team does not seek to conquer these rodents. Rather, the goal is to preserve the wetlands that support the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem and define the culture and economy of Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

The team’s work also benefits the region’s economy as a whole. It’s estimated that nutria cost Maryland $4 million in lost revenue in 2004 alone. The Bay’s crab and oyster fisheries are just two of countless industries that depend on coastal wetlands. The natural filtering capabilities of marsh plants cost millions of dollars to imitate with wastewater treatment plants. Nutria eradication doesn’t just save our wetlands; it also saves our money.

Do you have nutria on your property?

Nutria are often confused with beavers and muskrats, two native and ecologically important mammals. The Fish and Wildlife Service offers a nutria identification page on its website to help you distinguish the difference between these three similar-looking species.

If you think you may have nutria on your property, you should contact the Nutria Eradication Team.

“Nutes” are everywhere, from Louisiana to Seinfield

In Louisiana, the nutria infestation problem is even worse. The current generation is carrying on the traditions of fur-bearing trappers thanks to the state’s Nutria Control Program, which pays trappers per nutria they collect. The state even promotes nutria trapping by providing recipes for dishes such as smoked nutria and nutria chili!

Real fur may no longer be a faux pas for the environmentally conscious fashionista. Coats and hats made from nutria fur are considered by many to be “green and guilt-free.” George Costanza thought so, anyway: in an episode of Seinfeld, he replaces Elaine’s lost sable hat with another made from the fur of this invasive rodent.

Comments

Hi Charlotte, it is possible that there are nutria near the Echo Hill Outdoor School but unlikely. I suggest contacting them if you'd like to learn more. https://www.ehos.org/

Is there nutria that can be found at echo hill outdoor school. It is located on the eastern shore in Maryland towards the top.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories