Six ways African-American history helped shape the Chesapeake

In the Chesapeake Bay region, the African-Americans who lived and worked here helped define our history.

Each February, we celebrate Black History Month, but we often don’t take the time to reflect on the important people and events in black history that occurred right in our backyards. In the Chesapeake Bay region, the African-Americans who lived and worked here helped define our history.

Keep reading to learn more about six key events, people and occupations that influenced the history of the Chesapeake and the entire nation.

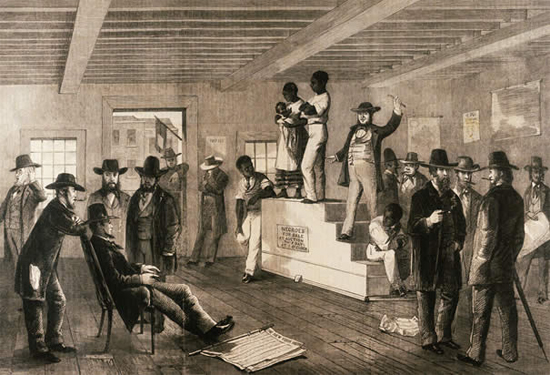

Slavery

Slavery in the Chesapeake Bay region began in 1619, when a Dutch ship carrying 20 African men arrived at Jamestown, Virginia. These men were indentured servants, rather than slaves. Many eventually earned their freedom and went on to own land, trade, raise crops and livestock, defend their rights, and eventually hire their own servants.

(Image courtesy CORBIS/History.com)

Slaves were part of many great milestones in the Chesapeake region, such as rowing the Bay’s first ferry between the future sites of Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia, in 1636. By 1780, it is estimated that slaves made up approximately 40 percent of the population in the Chesapeake region.

In the 1800s, the Chesapeake region was on the brink of controversy over slavery. The northern Bay watershed states were considered “free states” that did not support slavery, while the southern states were “slave states.” This division foreshadowed the battles to be fought in the region during the Civil War.

Civil War

As the Civil War progressed, the Union Army was suffering from increasing numbers of casualties and needed reinforcements. Blacks were granted the right to serve in the Union Army and fought in battles throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

In Maryland, 8,700 men served in six black regiments that played major roles in Union battle plans. The 36th U.S. Colored Infantry guarded the Confederate prison at Point Lookout and disabled Confederate torpedoes in the lower Chesapeake Bay.

More than 180,000 black men served in the Union Army and 18,000 black men in the Union Navy. Twenty-one of these men were awarded the highest military honor in the United States, the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where she lived until she escaped in 1849. After escaping from slavery, she returned to the South 19 times to help other slaves along the Underground Railroad.

As part of the Underground Railroad, a network of safe houses was formed and slaves were transported with the help of ship captains in Maryland, Delaware and Virginia, as well as other slaves working on boats. For many slaves, the Potomac River, the Susquehanna River and the Chesapeake Bay were vital links in the route to freedom along the Underground Railroad.

Frederick Douglass

Like Tubman, Frederick Douglass was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. In his first two attempts to escape slavery, Douglass and five other men planned to canoe up the Chesapeake Bay into Pennsylvania, but another slave turned them in. Eventually, Douglass was brought to freedom on a steamboat traveling from Delaware to Pennsylvania.

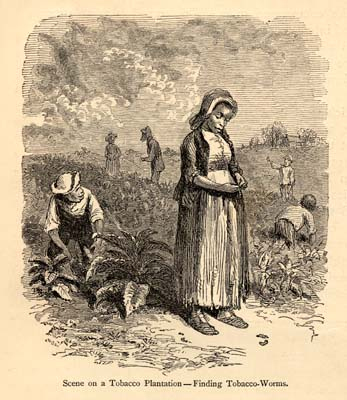

Tobacco plantations

In colonial times, tobacco was the mainstay of the economies of Maryland and Virginia. Many of the workers at tobacco plantations were slaves or indentured servants from Africa. Plantations were often located along the Chesapeake’s rivers, where soil quality was better and tobacco could be transported via local waterways.

(Image courtesy The Great South/Documenting the American South)

Oystering and seafood processing

Once the Chesapeake’s tobacco and agricultural industries began to decline at the end of the 18th century, blacks turned to the water to make a living, ultimately helping the region’s economy and cultural history flourish.

By the 1860s, the Chesapeake Bay was the United States’ primary source of oysters, which created plenty of opportunities for black watermen to make a living shucking oysters, processing seafood and even building boats for the industry. New African-American communities formed along the Bay’s shores, creating cultural and economic centers for blacks in the area. Their traditions became part of the local fishing industry, and many of them still exist today.

Comments

Where are these black communities on the bay?

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories