Boats of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is home to a diverse cast of boats, many of which are so unique to the area that you won’t find them in any other region. For centuries, different vessels have been invented to suit the needs of fisherman, explorers, athletes, scientists and anyone else taking to the water on a regular basis. Though some might be remnants of a bygone era, these 11 iconic watercraft have sealed themselves into the culture and history of the Chesapeake.

Log Canoe

Recognized as the Bay’s first workboat, log canoes once filled the estuary as watermen sailed about in search of fish and shellfish. They are usually made from three to five hollowed out logs that are fastened together and shaped into a hull—a simple but effective design based on similar boats built by the Powhatan Indians. One or two large masts jut out from the center of the boat, and sails capture the wind and use it as a propellant. Most log canoes that exist today have been retired from their working lives and are instead sailed in novelty races.

Bugeye

In the early 1800s, oyster dredging was banned in the Bay, so oystermen relied on log canoes to navigate the waters and used oyster tongs to snag the popular bivalve. When bans began to lift, a new type of boat was needed to be powerful enough to haul a dredge but lean enough to navigate shallow waters where oysters are found. Thus spawned the bugeye, a unique Chesapeake Bay invention used in early oyster dredging until it was replaced by the cheaper, but just as effective, skipjack.

Skipjack

In the late 19th century, the skipjack—a popular work boat for watermen—saw a production boom as the Maryland oyster harvest reached an all-time peak of 15 million bushels. But as the Bay’s oyster population steadily declined, so did its skipjack fleet. There are 35 skipjacks left in the Bay region, many of them used for educational purposes (like the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s skipjack, Stanley Norman). The skipjack is as unique a Chesapeake boat as you’ll find—so much so that the state of Maryland named the skipjack its official state boat in 1985. All throughout Maryland’s Eastern Shore, you’ll find skipjack races being held.

Skiff

Skiffs are shallow, flat-bottomed boats recognizable by their sharp bow and square stern. These watercraft are made to move through tight tributaries and along the coastal areas of the Bay. While they can be used as workboats, skiffs are typically used for recreational fishing and other leisurely outings.

Deadrise

The official boat of Virginia, the deadrise is a traditional work boat used by watermen to catch blue crabs, fish and oysters. The vessel is marked by a sharp bow that expands down the hull into a large V shape and a square stern. This was developed to help the boat navigate the Chesapeake’s choppy waters. The deadrise is said to be an evolution of the skipjack, and at times is considered something of an ugly but effective sibling.

Research vessel

Restoring an ecosystem as complex as the one in the Bay watershed requires constant monitoring and assessment. Research vessels like the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s (UMCES) R/V Rachel Carson travels around the Bay collecting data on water quality, flora and fauna to help scientists gain a better understanding about how to improve restoration efforts. The vessel can support up to 28 people, including crew for daily operations, while 13 people can be accommodated for multi-day excursions.

Schooner

Schooners are sailing ships with two or more masts. They have a long history in the mid-Atlantic as workboats for the watermen who made their living harvesting oysters, blue crabs and fish from the Bay. In October, schooners can be seen racing 146 miles down the Bay from Annapolis, Maryland, to Hampton Roads, Virginia, as a part of the Great Chesapeake Bay Schooner Race. This race was started to draw attention to the Bay’s heritage and to support environmental education and restoration work.

Racing shell

The sport of rowing, often referred to as crew, is a popular pastime for many who live in the watershed. Rowing clubs such as the Eastern Shore Community Rowers, Chester River Rowing Club and the Central PA Rowing Association all exist in the watershed, while many of the region’s colleges and universities support competitive crew teams. While racing, athletes sit with their backs to the bow of the racing shell and face the stern, using oars to propel the boat forward in one unified team.

Cargo ship

The shipping industry has been critical to the mid-Atlantic economy since the colonial era when the region first started serving as a bridge between the northern and southern United States. In fact, the Bay is home to two of the country’s five major North Atlantic ports: Baltimore, Maryland, and Hampton Roads, Virginia. Cargo ships were created to transport large amounts of commodities and can range in size and capacity from several hundred tons to several hundred thousand tons.

Buyboats

You’d be hard pressed to find any buyboats out on the water today, but there was a time when you couldn’t toss an oyster shell without hitting one. Like the same suggests, buyboats were used to sail out on the water, buy oysters from watermen in the wintertime, and haul them back to shore to sell. During the summer, they were used to haul all kinds of heavy materials used by watermen and merchants.

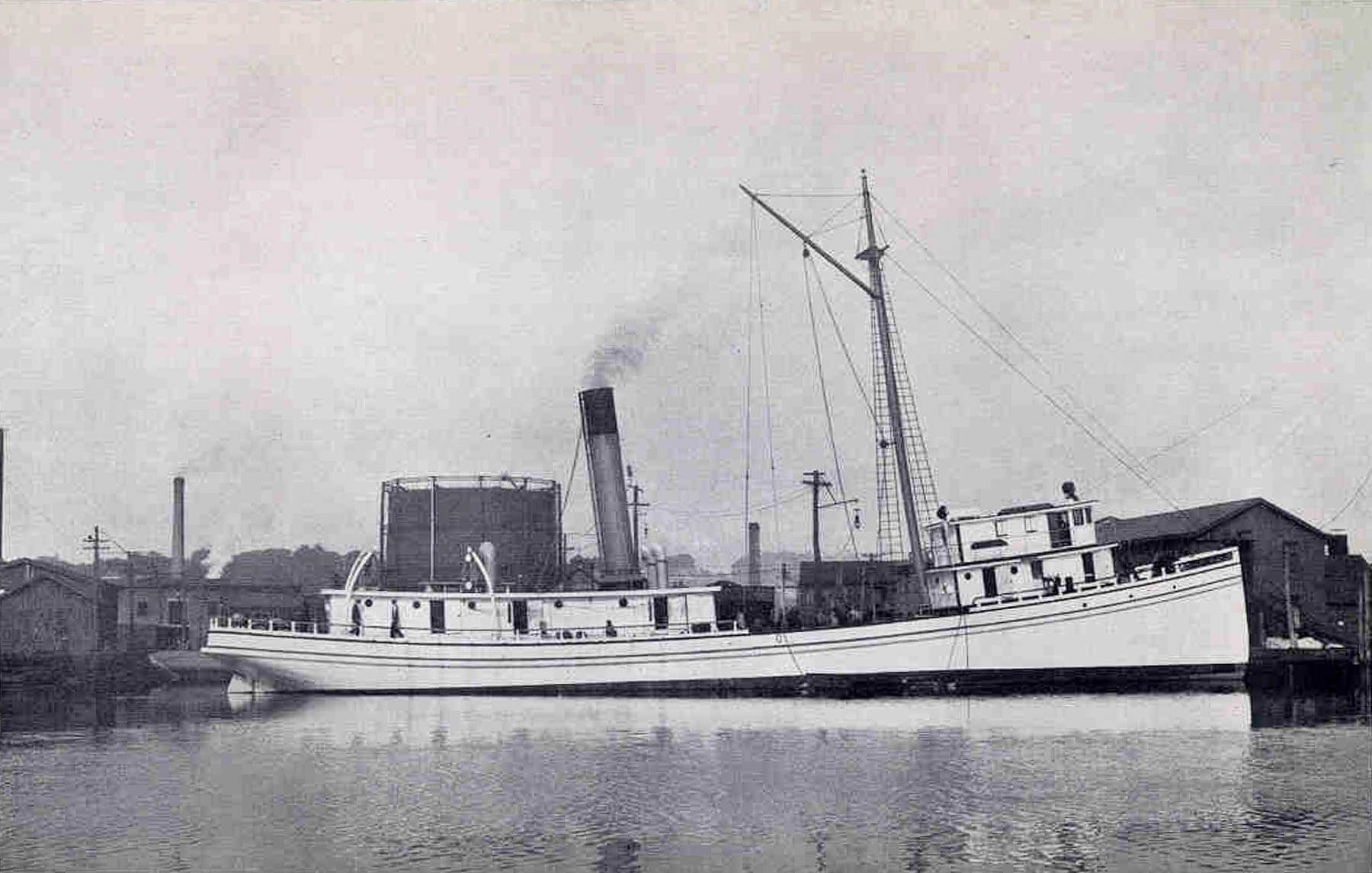

Menhaden steam ships

Menhaden steam ships have a complicated history. Before we knew how endangered and important to the food chain menhaden were, fishermen harvested them relentlessly, making the menhaden steam ships they piloted a well-known vessel. These ships are no longer used but are fondly remembered by many in the Chesapeake region for their bombastic appearance and the great plumes of smoke that marked their presence.

Want to learn more about the Chesapeake Bay? Visit our History page to read all about the region’s earliest inhabitants.

Comments

vedy good

Virginia's Government still doesn't understand (or care) about the importance of Menhaden to the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem.

Might want to include the bay steamers that ran up and down the bay and up the creeks and rivers. The transportation backbone of the region for more than a century. And don't forget all the ferries either!

Can anyone give me information on Artist George Wendt who drew these beautiful Chesapeake Bay Workboats in pen and ink in the 1970, s ? I have A collection of 4 and would like to know about the artist! Thank you !

Not all deadrises have square sterns. Many have the lovely round stern, and a few of the older girls still have the classic Diamond Stern.

And you forgot the gorgeous Hooper Island Draketails.

Hey Joseph, you have a sharp eye! We replaced the photo skiff photo. Thanks.

If you look closely, that's a CAROLINA SKIFF, which is a flat bottomed, fiberglass scow.

A real Chesapeake Bay skiff was built of qood, with a pointed bow, and most often a flat bottom, but they were also built as a modified deadrise.

I was very surprised that the Bugeye was not mentioned at all.

Seriously? You describe skiffs as flat-bottom boats and show a picture of a round-hulled boat. But worse, you talk about schooners on the Chesapeake Bay and show a picture of Alma, a scow schooner that only ever sailed on the San Francisco Bay and some tributaries. That's 2,500 miles away from the Chesapeake. Surely you can do better than this!

Yes dont forget the Buyboats and Dont forget about the Pungy Schooners..They were small, bay - built 1 to 2 masted schooners with flush decks, low sides and deep draft with big round bilge bellies for hauling cargo offshore , up and down the coast and to Baltimore from Bermuda ..They used to haul fruit from Bermuda back when one had to get fresh fruit or not get it at all... The big cargo freighters didn't bother with the short run to Bermuda to get fruit..they cost too much to operate so they had to get paid more for long hauls of more expensive cargos..They left the Bermuda runs to the little "bannana boats" , the Pungy boats..There are no authentic Pungy's left afloat, but the "Lady Maryland" is thought to be an accurate replica. Some clever wood boat builder ought to make a yacht version or two. Good luck finding the drawings for one , although one drawing does exist..A boat commissioned in Virginia in about 1850..

Very nice! Dont forget about the old Buy Boats and Menhaden Steam Ships.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories