Unseen danger leads to eagle deaths

How fragmenting lead bullets cause the toxic heavy metal to enter the food system

“You are controlling each element of yourself; you’re hearing your breath. You can hear a mouse rustle in the leaves. You can hear all the woodpeckers – the small ones, not just the Pileated. You hear the wind – is there a new sound inside it? You pay attention to all the different little things.”

To an environmentalist, psychologist or therapist, this may sound like forest bathing, the preventative health measure and act of nature healing born in Japan. Nature therapy has been incorporated into countless health practices and wellness groups across the world. Yet Sommer Morgenstern, West Virginia resident and vibrant mother of two, is actually describing what it is like to be a hunter.

“Hunting is like sitting down and talking to your grandmother,” Morgenstern offered. “You pay attention to what your grandmother is saying.” When you are hunting, she says, “You pay attention to what the woods are saying.”

Yet for all the connections with nature and careful motion of hunting, recent findings are uncovering an unintended consequence of how we hunt: lead poisoning.

Of all the bald eagles the Minnesota Raptor Center sees each year for rehabilitation, 90 percent have elevated lead levels in their blood. Of those birds, 25 percent had lead levels sufficiently high enough that they could not recover, and either succumbed to the toxic metal or were euthanized. Wildlife clinics in multiple states are seeing similar numbers.

The end is not pretty. “A lead poisoning death,” admits Jessica Conley, Maryland State Park ranger at Tuckahoe State Park’s aviary, “is slow, painful and takes weeks. Lead is a neurotoxin;” she continues uncomfortably, “an eagle with lead poisoning gets lethargic, loses muscle control, has neurological issues and eventually can’t fly. You will see an eagle walking almost drunkenly, with a lolling head or going in circles. Most end up starving to death.”

How is lead entering the system?

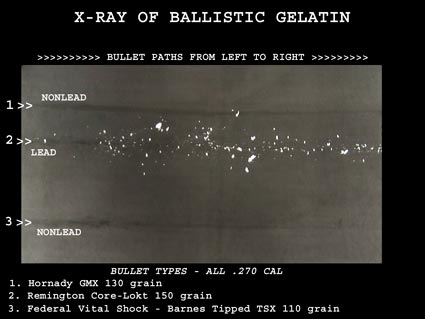

In 2009, the Minnesota Raptor Center completed a study which found a connection to deer hunting. Lead bullets were fragmenting into pieces too small for the naked eye to see and traveling much farther than previously supposed—up to 14 inches past the bullet entry site.

Scott VanArsdale, a lifelong eagle specialist formerly of the New York Department of Conservation, explains further. “Field dressing,” he instructs, referring to the initial removal of organs that a hunter performs in the field, “is necessary to keep the quality of the venison. A hunter will think, ‘the deer came from the wild’,” continues VanArsdale, speaking from experience. “’I don’t want it to go to a landfill, so I will dump it back in the wild.’” The bullet fragments, too small for a hunter to notice during their customary bullet recovery, pepper the gut piles. Eagles, as opportunistic scavengers, belly up to these feasts like a buffet, where their stomach acids will then leech the lead into the birds’ blood. A piece of lead the size of a grain of rice is enough to kill an eagle.

Morgenstern has been hunting since she was a child and is preparing her boys – too young yet to join – to be responsible in the field. When she says the phrase “the first rule of gun safety,” her two-year-old immediately pipes up, “treat every gun as if it is loaded.” Morgenstern understands hunting and her responsibility to the future, and appreciates the wonder of the natural world. She lights up when recounting the occasions she has seen the secretive and elusive golden eagles out in the wild. Outside of rangers, few individuals have the privileged access to wildlife on par with a hunter. When asked about the findings on lead fragmentation or the impact of lead poisoning on raptors, however, her answer highlights a gap in the research communication: “Goodness!” she exclaims, “I have not heard about that at all, no.”

The raptor data and lead studies are just barely a decade old, and there is a long way to go before the news spreads where it needs. Hunters are not hearing the lead fragmentation news, yet as Morgenstern puts it, “hunters are probably the most concerned with conservation because they are the ones out using it and want to keep the land and animals healthy.”

What you can do

There are some measures that hunters can take in the field to minimize damage. “When field dressing,” says VanArsdale, “what you can do is backpack the guts out, or bury and cover [the gut pile]. Or, put the pile into very thick brush and cover, as eagles don’t like going into the deep brush or inaccessible areas. Do the same things with the discards.”

Minimizing eagle access to gut piles will help to lessen the exposure of our national birds to the dangers of lead poisoning, but it will not address the lead fragments which remain in the pieces used for venison burger, or which occasionally even make their way into venison steaks. Though the CDC has set thresholds for when to take action, there is no safe limit for lead exposure.

Lower income communities, long plagued by the dangers of lead exposure from lead paint or subpar water pipes, can be doubly hit by the altruism of the hunter population. Hunters the country over supply much of the meat for food pantries through donation programs. As a result of the recent data, we now know that hunter families, the poor in our communities and our eagles are being exposed to lead consumption and potential poisoning.

Hunters take great care to kill quickly and with as little pain to the animal as possible. Copper bullets, originally intended for big game hunts due to their accuracy and deadly force, are excellent alternatives to lead shot. Though slightly more expensive than lead, copper bullets do not fragment in the same manner and offer a highly efficient kill. As concern over lead poisoning has become more pronounced, more manufacturers are beginning to offer nonlead ammunition for use in the field.

Would you like to make a difference for eagles and patrons of food pantries? Consider gifting a hunter with copper bullets. If you would like to do more, however – spread the word about the risks of lead and, in turn, gain valuable insight on nature from an incredible conservationist – have a conversation with a hunter.

Comments

I love this its amazing

Humans are potentially at risk. The harm to eagles is current, documented and lethal, but eagles are by no means the only beings affected. Due to their particular biological makeup, eagles and other raptors become terminally poisoned at low doses, making it an acute situation. Humans do not show the same immediate and devastating symptoms, but lead levels are shown to be much higher in those consuming game meat—particularly ground burger game. There is also the concern that, for humans, small amounts of lead over time can do more harm than a large amount at once.

The "What you can do" section of the article discusses the exposure of humans to lead levels in game meat and link to an article about human ingestion. In this Iowa investigation, it was found that some samples of deer meat showed lead levels up to 194 times higher than the threshold set by European Food Safety Agency for lead levels in meat. It went on to disclose that the state was not looking at game meat as a source of lead for the community, and quoted University of Colorado medical professor Michael Kosnett as stating "You lose more I.Q. points at low levels of exposure, per increment of blood lead, than you do at higher levels."

The "How is lead entering the system?" section links to an article in Scientific American about the amount of lead present in wild meat. This article quotes Dr. William Cornatzer, a hunter, on his reaction to seeing evidence of lead poisoning in condors and the immediate link he made to the lead he and his family would have ingested, saying, "I knew good and well after seeing that image that I had been eating a lot of lead fragments over the years."

Hunting helps to stabilize the deer population, creates revenue for conservation and stewards of the environment through hunters, and provides an excellent source of lean meat—though as we all discover new information about unintended consequences and harms, such as the findings on lead fragmentation, we can continually update our practices for the good of both humans and wildlife.

Iowa investigation of human lead levels from game meat: http://www.kwqc.com/content/news/TV-6-Investigates-Lead-in-venion-Iowa-health-officials-actions-421225163.html

Scientific American article on lead exposure from wild meat consumption: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wild-game-deer-venison-condors-meat-lead-ammunition-ban/

I am wondering why I see articles like this on the potential harm to eagles from lead ammunition, but I have never seen an article about potential harm to humans. It only seems logical that if raptors are poisoned by lead ammunition wouldn’t humans be also ?

I suppose my ultimate concern is without stating clearly that lead poisoning is an insignificant, mortality factor for raptor populations, the general, human population can easily be led to believe deer hunters are wantonly killing birds of prey. A simple Google search for "lead poisoning, eagles" brings up articles by National Geographic, The Washington Post, and The Guardian on the matter. That being said, I will now hunt with copper bullets for deer; I just wish more coverage was devoted to plummeting small, game populations which coincidentally, are prey for raptors.

Great question, Vince! Connecting landscapes to provide habitat is imperative to having a healthy watershed. The Bay Program's Vital Habitats Goal Implementation Team, along with its partners, is dedicated to restoring a network of habitats for vital species. You can read more about the Vital Habitats Team in this highlight article: https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/by_supporting_key_habitats_we_support_the_ecosystem.

Lead poisoning is not a significant mortality factor for the eagle population, but it is a completely preventable and painful death for those that are affected. The implications of lead contamination extend to humans, who are also ingesting lead fragments in venison: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wild-game-deer-venison-condors-meat-lead-ammunition-ban/.

I like the thoughtfulness and balance of this article. My only question, however, is lead poisoning a significant stressor/mortality factor for the entire population? With raptor's amazing comeback in response to federal protections and rapidly declining small game populations, is lead poisoning in a small portion of raptors truly a cause for concern when populations for these birds of prey are literally soaring? As a hunter, I would like to see more attention paid to fragmented landscapes and reduced habitat for small game as these animals don't have federal protections such as eagles, hawks, and falcons.

Eagles are often highlighted for this issue as our national bird, but most avian scavengers (vultures, ravens, condors out west) also experience these high lead levels. In New England, the leading cause of loon death is lead poisoning—in this case, from lead tackle rather than ammunition. Birds are extremely susceptible to lead, and the damage is extensive.

I found only a single study addressing large carnivores. Possibly because their diets are more varied, they are larger, and they have different biological symptoms, they are not as susceptible as our birds. Humans, too, ingest lead in venison, but the effects are not as immediately apparent as they are with birds. Grizzlies had higher lead levels, but the cause is still unknown because it did not change with the hunting seasons.

As for secondary ingestion, lead is eventually stored in the bones of an animal. If a large predator were eating the bones of a lead-contaminated smaller animal (not usually the case), the predator's lead levels would undoubtedly be much higher. Biological magnification (levels being higher in an animal that eats multiple contaminated animals) does not seem to be occurring with lead toxicity, though there was little research available for wildlife outside of birds on the topic of lead.

Ravens: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4229082/#pone.0111546-Gordon1

Loons: http://www.audubon.org/news/toxic-fishing-tackle-hampering-loon-recovery-new-hampshire

Large carnivore study: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1634&context=etd

(Bottom of page) Links to additional raptor, human, other wildlife studies: https://www.nps.gov/pinn/learn/nature/leadinfo.htm

Wild Meat Raises Lead Exposure: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wild-game-deer-venison-condors-meat-lead-ammunition-ban/

Thanks Caitlyn, I did not realize this is an issue. It makes a lot of sense though. Having hunted my whole life and left lots of gut piles in the woods, I wonder, along w Lloyd, what the repercussions are with the animals that he mentioned and even opossums and buzzards. I often have seen those feasting on the leftovers.

This kind of makes bow hunting a little more environmental for all animials. I will think about copper bullets now.thanks

Caitlyn, Appreciated the article.

Some common sense, little effort remedies were offered that I think would or could be well received by general hunting population with a round of education. ( i.e. in Pennsylvania a Hunter / Trapper Educational course would be appropriate forum )

A follow up question?? Do you have any data on lead levels in higher food chain predators such as fox, coyote, bears ??

Just a thought. Lloyd

Great information and tone in this article and it is important to be having this conversation. I'm hearing more and more about lead in the environment after there had been a decline for many years.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories