Weed warriors fight for forest health

In early spring, as a forest wakes up from its winter slumber, a wave of invaders reveal themselves. The green vegetation of multiflora rose, Japanese honeysuckle, Asiatic bittersweet, wineberry and other invasive species get an aggressive head start while most native plants are still dormant. Left alone, they lay siege to native biodiversity and can threaten the health of an entire forest.

A silver lining is that many invasive plants’ early green leaves make them an easily visible target for people ready to enter the fight against them. Weed Warrior programs have sprung up almost as fast as the plants they seek to eradicate from well-loved woods and trails.

“Not as fast as invasives are, but we’re spreading,” said Bud Reaves, a forester in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Reaves founded the Anne Arundel Weed Resistance in 2017 after many local watershed organizations recognized the need for a Weed Warrior program.

There are many different programs that independently use the Weed Warrior moniker, spread across the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Typically, they work by training volunteer stewards in invasive species identification, removal methods and tool safety, usually through several hours of classroom and field practice. Trained volunteers can then lead events in local parks or public land, so that more and more people know how to recognize and address the problem.

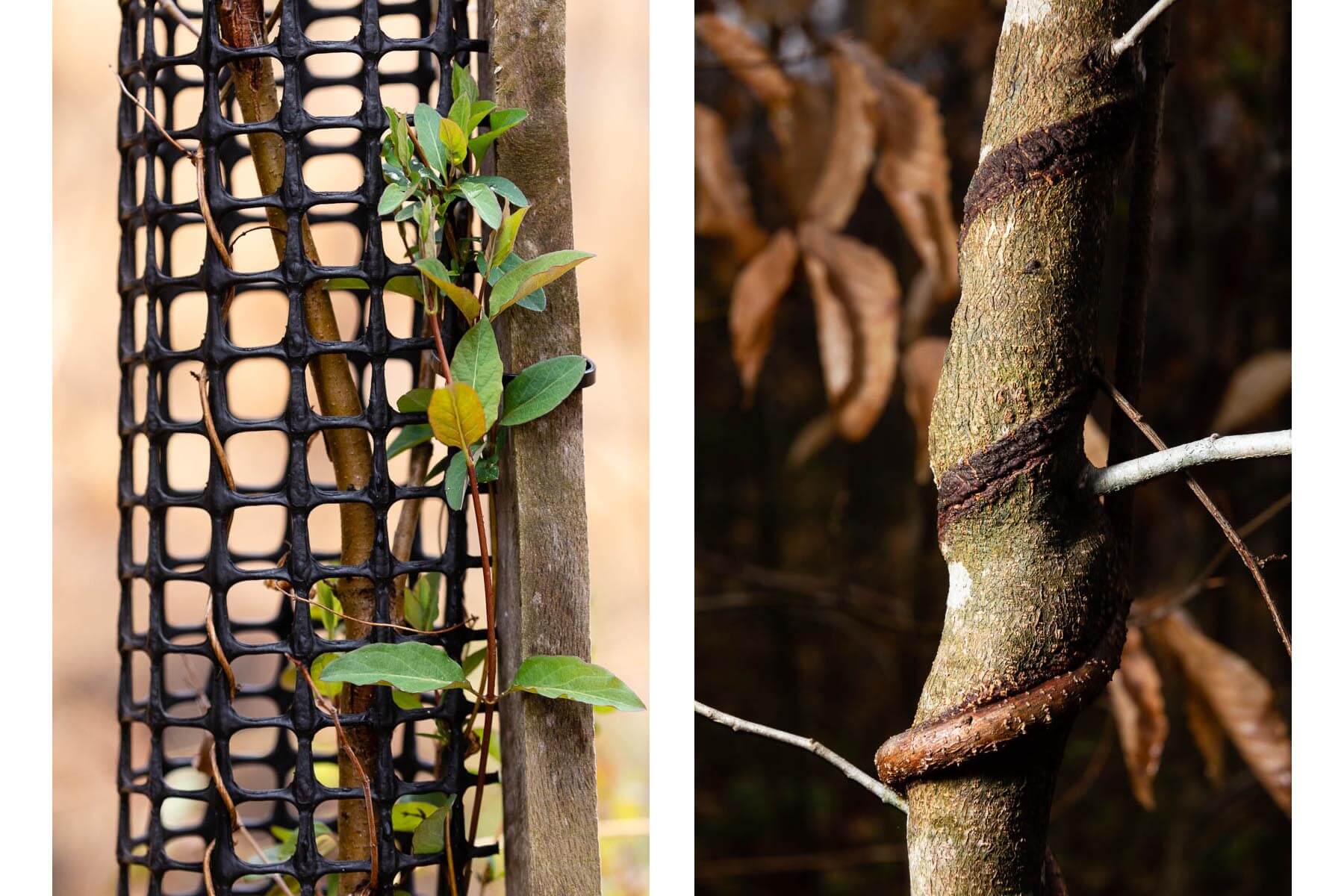

“You shouldn't see vines hanging from trees everywhere,” Reaves said. “That's not normal.”

Seedlings in a healthy forest are supposed to emerge and eventually survive to become adult trees, constantly regenerating a healthy forest canopy.

“And that wasn't happening because invasives were strangling them and shading them out and keeping them from growing,” Reaves said, adding that heavy browsing of native species by white-tailed deer only adds to the problem.

By crowding out native plants that support insects and wildlife, invasive species create a forest with less biodiversity overall. Trees also provide the best protection for aquatic life and help absorb pollution that would otherwise reach waterways and the Chesapeake Bay downstream.

“Forests in general, they're the best thing the [Chesapeake] Bay has going for it,” Reaves said.

Early spring is a great time for weed pulling for several reasons. The weather is not yet sweltering, the vegetation is not yet too thick to navigate and spring rains tend to make forest soils soft enough to easily pull many invasives out from the roots.

It’s also a nice time of year to observe nature. Reaves and Lara Mulvaney, a Master Watershed Steward volunteer, recently led an early spring gathering for the Weed Resistance. Several trainees learned how to pull and cut vines and shrubs on county land above the site of a major stream restoration on Flat Creek. The volunteers were treated to the calls of American toads and leopard frogs spawning along the waterway and paused to watch a black rat snake calmly slither away.

Reaves and Mulvaney showed the group how to identify invasive vines like English ivy from native ones like wild grape and poison ivy. Rather than pulling down vines that can reach all the way to the tops of trees, it’s easier and less damaging to cut out a large section at the base of the vine. Eventually the plant will dry up and fall away on its own.

After a few hours, the group had made a sizable dent. Looking in one direction, the hillside remained a formidable bramble of invasives. But in the other direction, a spacious forest understory looked more like it should—spacious, dotted by native beeches and spicebush.

“I sort of became aware that what most people see is the fringe of the woods and that it's often in bad condition,” said Mulvaney, who was part of the Weed Resistance’s first training group in 2017 and has kept up the fight in her community since then. “My motivation was to keep the woods in good condition and fight back the front—and sort of expose people to what a healthy woodland would look like.”

Mulvaney knows that the problem of invasive species is a daunting one, with no real end. But she has also seen victories along the way, like when she can convince neighbors to swap out harmful ornamental plants in their yards. Often, the seeds of those plants are spread by wildlife and take root in nearby forests, adding to the invasives. Mulvaney herself pulled English ivy from her wooded front yard and was surprised to see native mayapples emerge entirely on their own.

Those interested in keeping their green spaces healthy, Mulvaney said, should make weeding a routine in order to keep invasives from getting out of hand in the first place. And they should develop good relationships with their neighbors in order to turn them towards more sustainable landscaping choices. Ultimately the challenge of addressing invasive species is a marathon, not a sprint, and even professionals can’t solve the problem all at one time.

“The word to the wise would just be to pace yourself,” Mulvaney said.

Comments

GHreat post! By dedicating their time and effort to combat invasive species, weed warriors contribute significantly to the protection and restoration of forest ecosystems, helping to maintain the ecological balance and overall health of these vital natural resources.

Thank you for the AWESOME information and content! We have just recently got involved with the Weed Warriors program in Montgomery Co and are in the process of engaging more involvement in Frederick Co . A well needed act in ALL our forests and homes!

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories