What we’ve learned from exploring a century of nitrogen pollution

By 1950, the Chesapeake region had changed dramatically due the influx of people moving to the area. The watershed experienced massive deforestation, expansion of farmland and the growth of suburbs and cities. With all that change came an increase in stressors to local waterways—particularly nitrogen pollution—which continues to be one of the biggest impediments to restoring the Bay.

Nitrogen enters the water from sources like fertilizers, animal waste, wastewater, urban runoff and atmospheric deposition, which is when nitrogen in the air comes back down with precipitation or air particles. When found in too high amounts, nitrogen causes excessive algae growth, which blocks sunlight from reaching underwater plants. When the algae decomposes, it removes oxygen from the water which creates dead zones. Efforts to reduce nitrogen runoff is an ongoing battle as each jurisdiction in the Chesapeake Bay watershed has a limit on the amount of nitrogen that can enter their waters and flow into the Bay.

In 2021, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) researchers working with Chesapeake Bay Program scientists released an award-winning report that explores 100 years of nitrogen pollution. The report provides a unique, long-term perspective of the major drivers of nitrogen pollution—including climate change, hydrology, atmospheric deposition, land use, agriculture, developed areas and wastewater—from 1950 up to 2012, when the study started. The team then forecasted data out to 2050, resulting in a 100-year timeline of nitrogen pollution.

Five findings from the report

Pollution significantly grew from 1950-1980

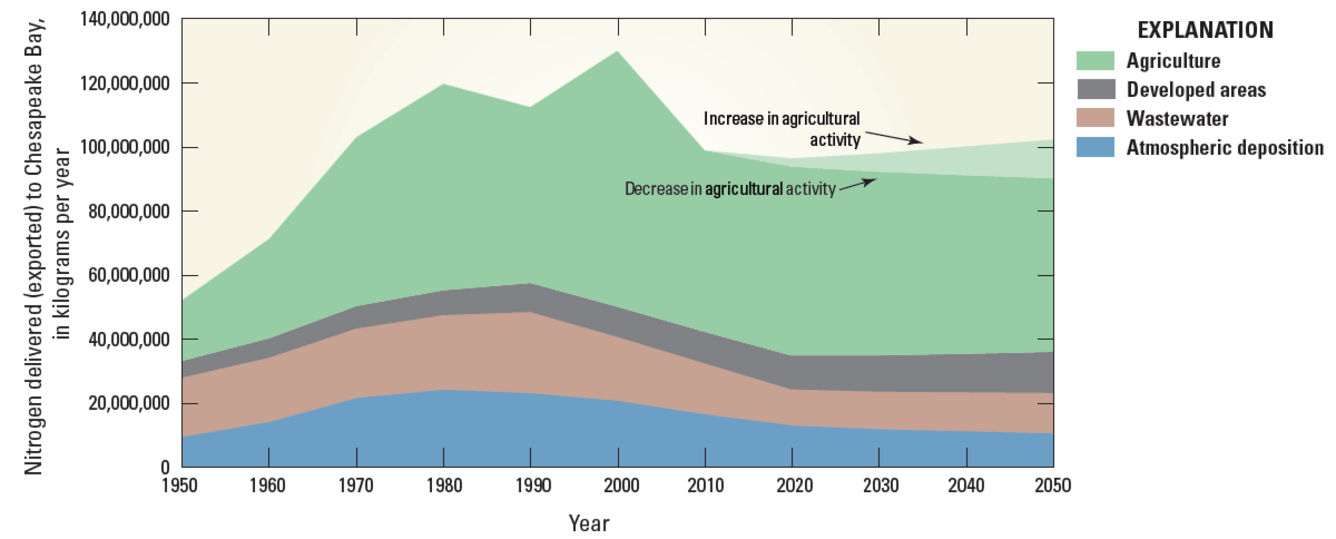

All sources of nitrogen to the Bay increased substantially from 1950 until the 1980s, but varied afterwards. From 1980 to 2012, for example, nitrogen pollution from atmospheric deposition and wastewater decreased, but agricultural sources fluctuated during the same time. Nitrogen pollution from developed areas grew slightly from 1980 to 1990, but decreased from 1990 to 2020. These findings show that pollution limits and restoration work has limited nitrogen pollution in some sectors, but that continued, long-term management is needed.

Upgrades to wastewater treatment made a big dent

From 1950 to 1990, the amount of nitrogen from wastewater being put into Chesapeake waters increased as the population grew. However, after 1990, the jurisdictions worked through the Chesapeake Bay Program to upgrade their facilities to better remove nitrogen from wastewater. Now, nitrogen from wastewater is lower than what it was in 1950 and is predicted to only have slight increases in proportion to population growth.

The Clean Air Act saved us from further pollution

Looking at atmospheric deposition, we see declines beginning in the 1980’s with the introduction of the Clean Air Act. The Clean Air Act put in place regulations that reduced air pollution from sources such as power plants and vehicles, which had a direct impact on water quality. However, there is opportunity for further reductions from sources like manure and fertilizer, which can result in air pollution when they vaporize.

Agriculture growth brought unprecedented nitrogen pollution

In the second half of the 20th century, the widespread use of fertilizer and intensification of animal farming grew significantly, resulting in unprecedented amounts of nitrogen pollution. The study shows that manure and fertilizer has continually increased from 1950 to 2012, resulting in more nitrogen in Bay waters. However, over the past few decades, Chesapeake Bay Program partners have worked with farmers to expand the variety and quantity of conservation practices that reduce nitrogen pollution. Working with farmers continues to be a focus of the Chesapeake Bay Program, especially those in Pennsylvania, where thousands of small farms contribute to pollution entering the Susquehanna River.

Greatest opportunities for nitrogen decreases are in agricultural and developed areas

Forecasting the next 50 years, researchers found that the greatest opportunities for reducing nitrogen pollution will be in agricultural and developed areas. On farms, this includes installing best management practices, such as cover crops and forest buffers that manage fertilizer and manure runoff. For urban areas, this includes implementing green infrastructure to soak up stormwater runoff, as well as enhancing wastewater treatment plants by separating pipe systems that handle sewer and stormwater into two different systems.

The next 50 years will be a critical time for the Chesapeake Bay watershed. To learn more about this USGS research click here to access the video or read the report. If you’d like to know how you can do your part to keep local waterways clean, visit our How To’s and Tips page.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories