Virginia seeks to retell the story of two segregated lakes

The Chesapeake Bay watershed is full of rich and inspiring history—but while there are some stories that get told again and again, others are nearly forgotten.

On a sunny day in early February, seventeen members of Black Girls Hike RVA visited Twin Lakes State Park in central Virginia for a special Black History Month trip. They were invited by park ranger Breanna Doll, who had been following the Virginia hiking group on social media and thought that they might enjoy hearing about the park’s history.

“I really had no idea how many people to expect,” Doll recalled thinking. “So I was excited when car after car pulled up that morning.”

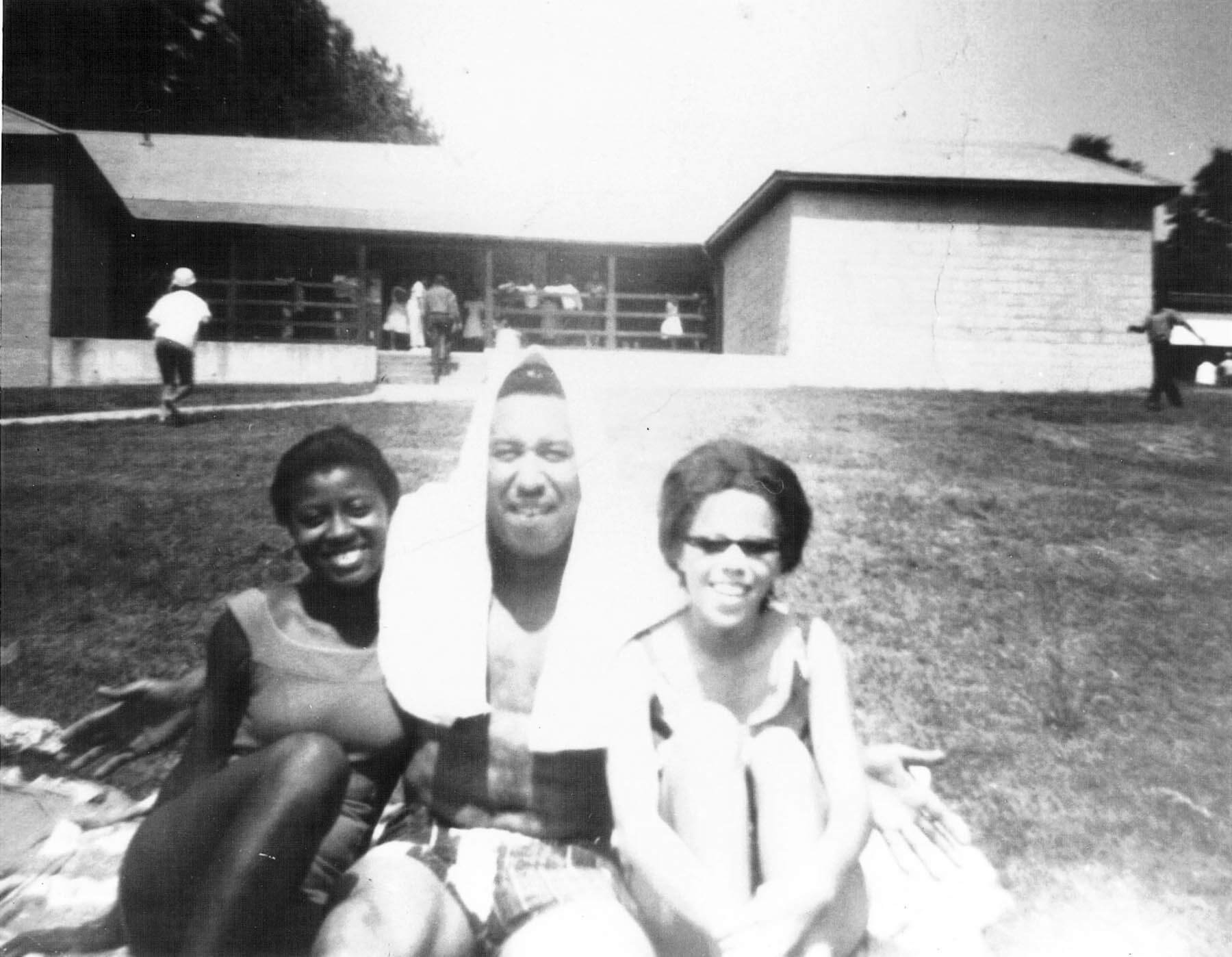

After walking the park’s longest trail, the hikers gathered near the visitor’s center where Doll brought out a small container filled with photographs and documents from back when the park's two lakes were segregated. As explained by Doll, the documents were all that they had from that time.

“It was barely enough artifacts to fit into a little mail carrier box,” said Shara Tucker, who co-founded Black Girls Hike RVA alongside fellow middle school teacher Nicole Boyd.

The black and white photos showed Black families camping, cooking, swimming and dancing at what was then known as Prince Edward State Park for Negroes. Doll told the hikers that before it allowed “colored” visitors, the park was built by an all Black Civilian Conservation Corps Company, and that it took one man’s civil rights protest for the segregated swimming hole to be turned into an official state park.

“This needs to be displayed and honored,” Boyd felt. “It’s a story that needs to be told.”

A civil rights victory spawns a state park

In 1948, a lawyer named Maceo Conrad Martin made a drive to Staunton River State Park knowing that he’d be denied entry based on the color of his skin.

He used this incident to file a lawsuit against the Commonwealth, arguing that Virginia was violating the law by not providing a "separate but equal" facility for Blacks. He won the case, and the state eventually chose Prince Edward Lake (today one of the two lakes at Twin Lakes State Park) as the place to build an official park.

The lake was already a popular swimming hole used by Black visitors, while its twin, Goodwin Lake, was used by Whites. Deciding to upgrade Prince Edward Lake to a state park, the Commonwealth constructed a restaurant, staff residences and offices, picnic shelters and overnight facilities around the lake. By 1950, Prince Edward State Park for Negroes was opened as Virginia's eighth state park.

For years, Prince Edward State Park was a top destination for Black Virginians in the time of segregation. Families camped, cooked and swam on hot summer days. The restaurant was converted into a popular dance hall that was booming on the weekends. Attendance rose from 16,000 in 1949 to over 52,000 in 1951.

“Prince Edward State Park for Negroes was the first (and for some time, the only) Virginia State Park accessible to people of color,” said Ranger Doll. “It wasn't uncommon for people from other states to visit the park, as it was often closer to their home than any other accessible park.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 integrated both Goodwin Lake Recreation Area and Prince Edward State Park, but the two continued to function as separate entities for more than a decade. It wasn’t until 1976 that the state park's boundaries changed and the two lakes became part of one park: Prince Edward and Goodwin Lake State Park.

Eventually, all swimming was moved to Goodwin Lake, with Prince Edward Lake being reserved for those renting cabins, and in 1986, the park was renamed to Twin Lakes State Park.

Today, the Twin Lakes State Park includes 548 acres and features the two lakes, a concession stand, a conference center, a campground, cabins, five trails, numerous picnic shelters and more. No distinctions between who uses what side of the park remain, though the story of Prince Edward Lake and Maceo Conrad Martin’s legal victory aren’t often observed by the park’s thousands of annual visitors.

Time to start telling the story

On the day Black Girls Hike RVA visited Twin Lakes, Ranger Doll shared with the group the park system’s plan to better share the park’s history.

According to Josh Ellington, central Virginia district manager for the Department of Conservation and Recreation, Twin Lakes is due for a new master plan, which gets updated every 10 years. One priority for the 2021 master plan is to better unite both sides of the park. There are currently two entrances, one to Prince Edward Lake, which is reserved for cabin rentals, and another to Goodwin Lake, which is a public swimming area. While the areas are no longer divided by race, they still feel geographically disconnected.

“People can come to Twin Lakes and go to Goodwin Lake and never even be exposed to Prince Edward or have the opportunity to learn about what happened there,” said Ellington.

To remedy this, the master plan includes concepts for creating a single entrance (which will also remove a road that goes through the park) and a welcome center that will display the civil rights history of Virginia's state parks. The plan also suggests turning an unused shelter at Prince Edward lake into an outdoor exhibit on Maceo Conrad Martin and the development of the segregated park.

These ideas are the most prominent changes within the master plan, which was slated to be updated in 2021. According to Ellington, the timing for the plan could not have come at a better time.

“The events that have occurred over the last 12 to 18 months have brought these conversations to the forefront,” said Ellington, referring to the rise in social and racial justice discourse following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans. “They’re still going to be difficult conversations, but people are open and ready to sit down and have them.”

According to Doll, the park can serve as a venue to tell the history of not only Black Virginians, but of those who first inhabited the area.

“Here at Twin Lakes, we've obviously got a great civil rights history to tell, but our story goes back further than that—we've also found spearpoints people were hunting with on this land more than 5,000 years ago,” she said.

On April 28, there will be a public meeting where members of the community can provide feedback on the master plan. Shara and Nicole will be a part of that meeting, and were invited to join the board after their visit in February.

The two hiking enthusiasts, who now share the story of the park with friends, colleagues and students, see the history of Prince Edward Lake as being important not just to Black women like themselves, but to everyone with a connection to the region.

“It’s not just the Black stories,” said Boyd, “It’s the story of Virginia.”

Comments

Like to know more history about Prince Edward Lake ( Green Bay) Our Church annual Picnic during the 50th and 60th’s Lots of happy times there.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories