Bay grasses continued to rise in 2023, much to the delight of fans like me

An environmental professional admits her own shortcoming

I’ve worked for the Chesapeake Bay Program for over eight years now, and I’m finally ready to reveal my deep, dark secret.

I really didn’t know anything about underwater grasses before I worked here.

I mean, I grew up outside of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, in the Pennsylvania mountains. My family would head to New England in the summer, where seaweed soup and lobster were go-to meals, not blue crabs. I studied environmental policy in college, where I didn’t have the privilege of participating in many field experiences. Those are legitimate excuses, right?

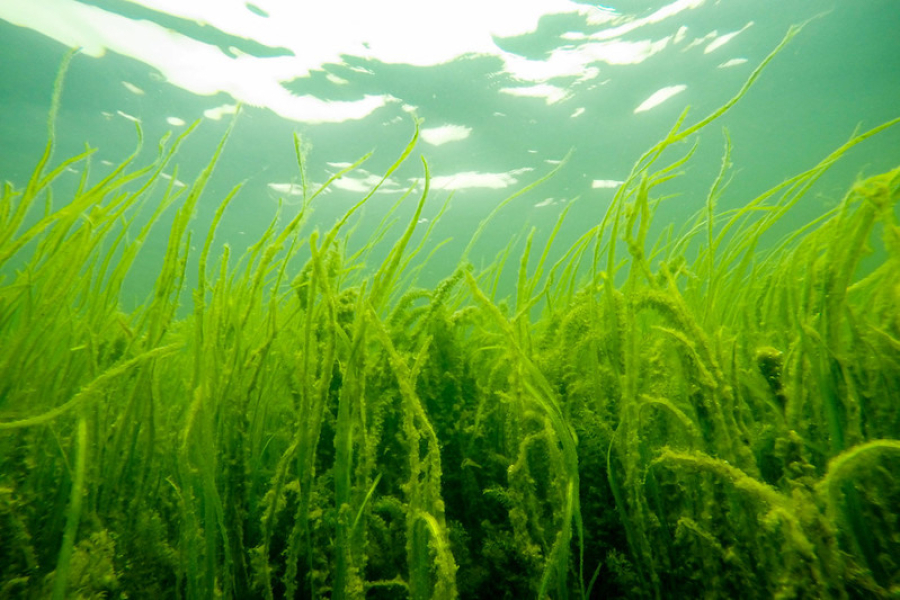

While I am ashamed to admit this fact now, I learned very quickly how important underwater grasses–otherwise known as submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV)--are to the Bay’s ecosystem. And then I became a superfan. I cheered alongside our scientists and experts when the acreage surpassed 100,000 acres–the first time in modern history–in 2017 and sadly reported the news that in 2019, SAV in the Bay had declined as much as 38% from the previous year. Last summer, I even participated in my first SAV survey in Mallows Bay in the Potomac River.

I am optimistic about the future of our grasses, especially knowing that they continue to rebound. In fact, the Chesapeake Bay Program announced today that the abundance of underwater grasses has continued to increase for the third straight year in a row. Scientists from the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) believe the Chesapeake Bay could have supported as many as 82,937 acres of underwater grasses in 2023. We say “could have” because while 79,234 acres were observed through an aerial survey and satellite imagery, portions of the Potomac River were not able to be mapped due to security restrictions. Using the acreage of grasses noted in that portion of the Potomac from the previous year gets us to the estimate of 82,937 acres.

But why are underwater grasses so important? They provide critters in the Bay with habitat and food, they add oxygen to the water, absorb nutrient pollution, trap sediment and help reduce erosion. SAV is directly linked with the Chesapeake’s blue crab population, as they provide habitat and key feeding grounds for juveniles, while offering refuge from predators.

Underwater grasses also are an excellent indicator of water quality. Since they are so heavily impacted by changes in the weather, seeing SAV bounce back after extreme rainfall or heavy river flows indicates that management actions taken by our partners across the watershed are working.

Water must be clear enough for sunlight to pass through and help the grasses grow. Too much nutrient pollution can cause excess algal blooms to grow, blocking the sunlight from reaching the underwater grasses, while sediment can smother them, causing the SAV to die off.

In 2023, SAV increased heavily in the Bay’s more salty waters. In the Polyhaline–or very salty waters–the acreage increased by 12%, which is the largest amount of grasses noted in this region since 2017.

“It’s been exciting to observe some tremendous expansion in some areas of the Polyhaline with eelgrass growing at depths we haven’t seen in decades.” says Christopher J. Patrick, director of the SAV Monitoring and Restoration Program at VIMS. “We often call these plants the canary in the coal mine for the Chesapeake, as they tell us a lot about how the Bay is doing.”

Follow along with me and root for the Bay’s grasses. Keep an eye on ChesapeakeProgress for the most up-to-date information or check out how to become a Chesapeake Bay SAV Watcher.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories