Sustainable harvests play a role in growing forests

By managing forests, Maryland is working toward a future with more trees

Cutting down trees hardly seems like the path to a future with more forests. But when done properly, managing forests with timber harvest in the Chesapeake Bay watershed is an essential part of meeting water quality and climate goals, in addition to providing social and economic benefits to communities that need them.

Like every state in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, Maryland is trying to grow its forests. And after decades of declines in its forest cover, a major study of Maryland’s forest cover and tree canopy shows the state has come tantalizingly close to reversing the trend. Maryland has stabilized its losses in part by making it more enticing for landowners to keep land as forest, instead of losing it permanently to development.

“The technical study did point out that the area where we gained the most forest was the lower [Eastern] Shore where we have the most active forest industry,” said Anne Hairston-Strang, state forester and director of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Forest Service.

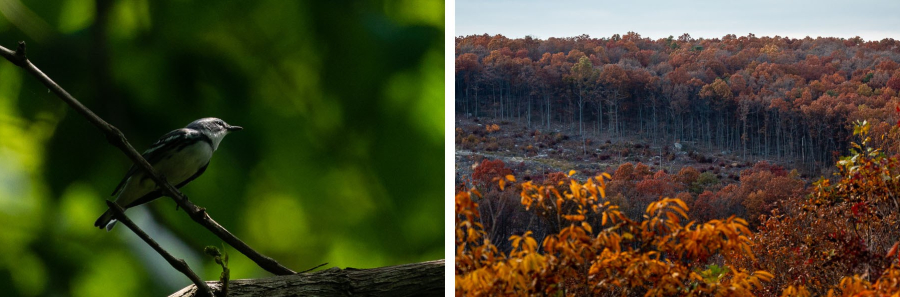

Managing a forest can take a number of approaches. Harvesting might involve a clear-cut, where all the trees in a precise area are taken. Maturing trees might be thinned to give higher performing stems more room to grow, to be harvested perhaps 50–70 years later. Or, certain species could be left to create wildlife habitat or to serve as “seed trees.” While replanting is common, a lot of forestry in Maryland also relies on natural regeneration from existing seeds.

Where harvesting should be avoided or practiced with additional precautions depends on the waterways nearby and the presence of sensitive species.

For example, preserving a riparian buffer—at minimum 100 feet, or perhaps 300 feet on steep, erodible slopes—is required to protect tidal waters, tidal wetlands and streams. Timber harvest within Maryland’s Critical Area requires an approved timber harvest plan. And the presence of habitat for forest interior-dwelling birds (FIDS) comes with additional considerations.

The value of young trees

Hairston-Strang, who has been with the Maryland Forest Service for nearly 30 years, says that “most people do not own forests, now, for that economic return.” But most people are interested in the possibility of selling timber, especially as life presents the periodic need for income to cover things like college, retirement or even a hospital bill.

And while the state certainly wants to add to its very mature forests, there is also a need for more young forests, which are created when a harvested area begins to regenerate.

“One of the other things declining is that young forest area,” Hairston-Strang said.

Many species rely on young forests for the unique habitat they provide. One example is the golden-winged warbler, which lives in more mature woodlands but then nests in the thick, shrubby vegetation of a regenerating young forest.

“We certainly have some [young forests] but we need enough to support that suite of species that uses that habitat,” Hairston-Strang said.

Young forests also regenerate quickly. A younger oak tree, for example, is more likely to sprout again from its stump when cut, compared with a 200–300 year old tree. Hairston-Strang points out that stump sprouts are a useful trick for quickly getting trees growing “above the deer” to avoid browsing pressure.

Balancing young and old forest is also important for carbon sequestration. Hairston-Strang compares it to having both growth stocks and bonds in your investment account.

“The growth stocks are your young forests, the bonds are your maturing and mature forests,” Hairston-Strang said.

While large, mature trees hold more carbon overall, the rate of carbon sequestration is faster in young trees. So if you only have big, old trees, “then you’re not building the [long-term] ability to keep that area going as a carbon sink.”

Hairston-Strang says one challenge in Maryland is that the proportion of natural mortality in forests—trees dying or falling over—is increasing as harvests are decreasing. As a result, “we see a gradual decline in the carbon sequestration rate.”

Another symptom of unmanaged forests is that when trees grow too close together and form dense stands, they are more vulnerable to the spread of pests and disease.

“Using forest management to thin out some trees promotes good forest health by allowing the remaining trees to grow bigger and be more resilient,” said Katherine Brownson, U.S. Forest Service liaison to the Chesapeake Bay Program.

A role for incentives

There is a lot of room for improvement in parts of the state, such as in central Maryland, where forest management is less common and invasive species have moved in.

A big challenge to increasing forest management, Brownson points out, is that there are limited markets for the low-value timber that is typically removed while managing young forests, which are composed of smaller trees. This can lead to management costs that are only partially offset by timber sales.

“Having ready access to local processing facilities is also essential, as exporting timber products to other states can further increase costs,” Brownson said.

Unfortunately, mill closures have become increasingly common. In February 2024, for example, Allegheny Wood Products in West Virginia announced its closure.

Hairston-Strang said that one positive step was when a Maryland mill reopened on the Eastern Shore in 2021.

“The sweet spot here is where you can…have strong, diverse markets that let you do good forest management and provide that incentive for landowners to keep it in forest,” Hairston-Strang said, adding that with the right motivation, landowners might even invest in expanding their forests.

Landowner objectives might include management for wildlife, perhaps to boost hunting opportunities for white-tailed deer and wild turkey or to support young forest species like the golden-winged warbler or bobwhite quail, which depend on both young and old forest habitat to survive. A diversity of objectives means a diversity of habitat, and less risk of, say, a spongy moth infestation or forest fire wiping out large blocks of forest.

In any case, Hairston-Strang says that someone interested in managing their forested land should reach out to a professional, licensed forester, in particular someone who “has experience managing for their objectives.” A forest management plan is also recommended, and there are tax abatement programs associated with having one.

Hairston-Strang believes the positive impacts of forest management follow the flow of water from the land upstream to the Chesapeake Bay. And if more counties in Maryland increase their management efforts, incorporating the social and economic elements into the environmental benefits, Hairston-Strang hopes to see a “net gain of forest area” and a lot of trees in the state’s future.

“That’s a win for the Bay and that’s a win for the climate.”

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories