The Chesapeake in 2022: Top stories from the Bay Program partnership

Take a look at the most popular articles we released in 2022!

Each month we bring you new stories about the Chesapeake Bay watershed, a region that is filled with incredible wildlife, fascinating cultures and hopeful efforts to restore the land and water. This roundup of the year’s most popular articles covers all that and more. Browse through and leave a comment about which stories mean the most to you!

A new park in Delaware honors the ‘people of the tidewater’

After years of thoughtful collaboration between the University of Delaware, Delaware Sea Grant, the town of Laurel and the Nanticoke Indian Tribe, a new park was opened in honor of the region’s early inhabitants. Animal-shaped installations—including a giant wooden beaver and turtle—were chosen based on their prevalence in Nanticoke lore. The park overlooks a tributary of the Nanticoke River and will be added to in the future.

A thoughtful approach to restoration is giving one community more days at the beach

A new 970-foot living shoreline was installed at the community beach in Cape St. Claire, a suburb of Annapolis, Maryland, to help with erosion. Living shorelines are a growing environmental practice that reduce erosion, improve water quality and add habitat for wildlife. The engineering firm Biohabitats, Inc. installed the shoreline and the nonprofit Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay helped acquire funding and manage the project.

Seven locations around the watershed that hold a connection to the Underground Railroad

For Black History Month, we took a look at seven historic landmarks connected to the Underground Railroad, an informal network of routes, safehouses and resources used by enslaved African-Americans to journey to their freedom. Churches harboring escapees, the site of John Brown’s Raid, a riverside park where Harriet Tubman herself located an enslaved woman seeking freedom and more can be found across the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Five reasons bald eagles are wild about the Chesapeake Bay watershed

The abundance of bald eagles in the Chesapeake Bay watershed has grown significantly over the past few decades, growing from 60 breeding pairs in the 1970s to approximately 3,000 in 2021! Our article from 2022 covers all the reasons that this iconic bird thrives on the Bay’s tributaries.

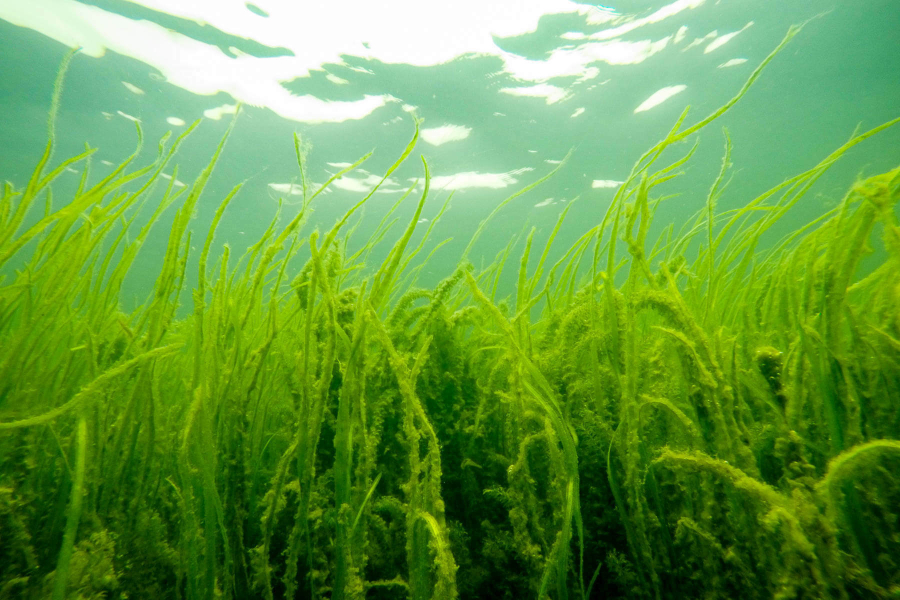

What do more underwater grasses mean for Chesapeake wildlife?

This year, we reported that the abundance of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) in the Chesapeake Bay was 9% higher in 2021 than the previous year. SAV acts as nursery habitat for juvenile blue crabs, which makes the vegetation critical to the having a sustainable blue crab harvest. This article covers the connection between SAV and the Bay’s keystone species.

Photo Essay: Home to rare wildlife and small towns, a rural region plans for the future

Some of the cleanest rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed can be found in New York’s Butternut Valley, a rural landscape that encompasses 10 unique municipalities. Our photo essay on the region explores the hardships of an area where farms are closing and young people are leaving, as well as the opportunities for tourism in such a pristine part of New York.

Between two rivers, a city’s hopes are tied to healthy waters

In another striking photo essay, we tell the story of Hopewell, Virginia, a working-class town that’s seen major improvements to water quality and recreation. In the photo essay you’ll hear from local residents, conservationists working in the area and community leaders including Councilmember Jasmine Gore, current chair of the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Local Government Advisory Committee.

Mental health initiative connects UMD students with the outdoors

A growing initiative to promote the mental health benefits of nature, known as Nature Rx, has taken up roots at the University of Maryland. Two of the university’s professors share the vision for this new initiative, which includes nature walks, forest bathing, gardening and a partnership with the school’s medical students and mental health counselors.

West Virginia landowner collaborates with nonprofit to restore brook trout habitat

Determined to bring brook trout back to a stream that runs through his property, a West Virginia landowner worked with Trout Unlimited to implement a variety of conservation practices. Funded by the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Small Watershed Grants program, the project included new stream fencing, tree planting and restoration of the streambank.

Oyster reefs restored in seven Bay tributaries; four to go

This year we were excited to announce that the Chesapeake Bay Program has officially restored oyster habitat in seven Chesapeake Bay tributaries. Partners on this team have collaborated since 2010 to create these crucial habitats in both Maryland and Virginia. By 2025, we’re expected to have restored habitat in four more rivers.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories