The more the merrier when it comes to underwater grass species in the Bay

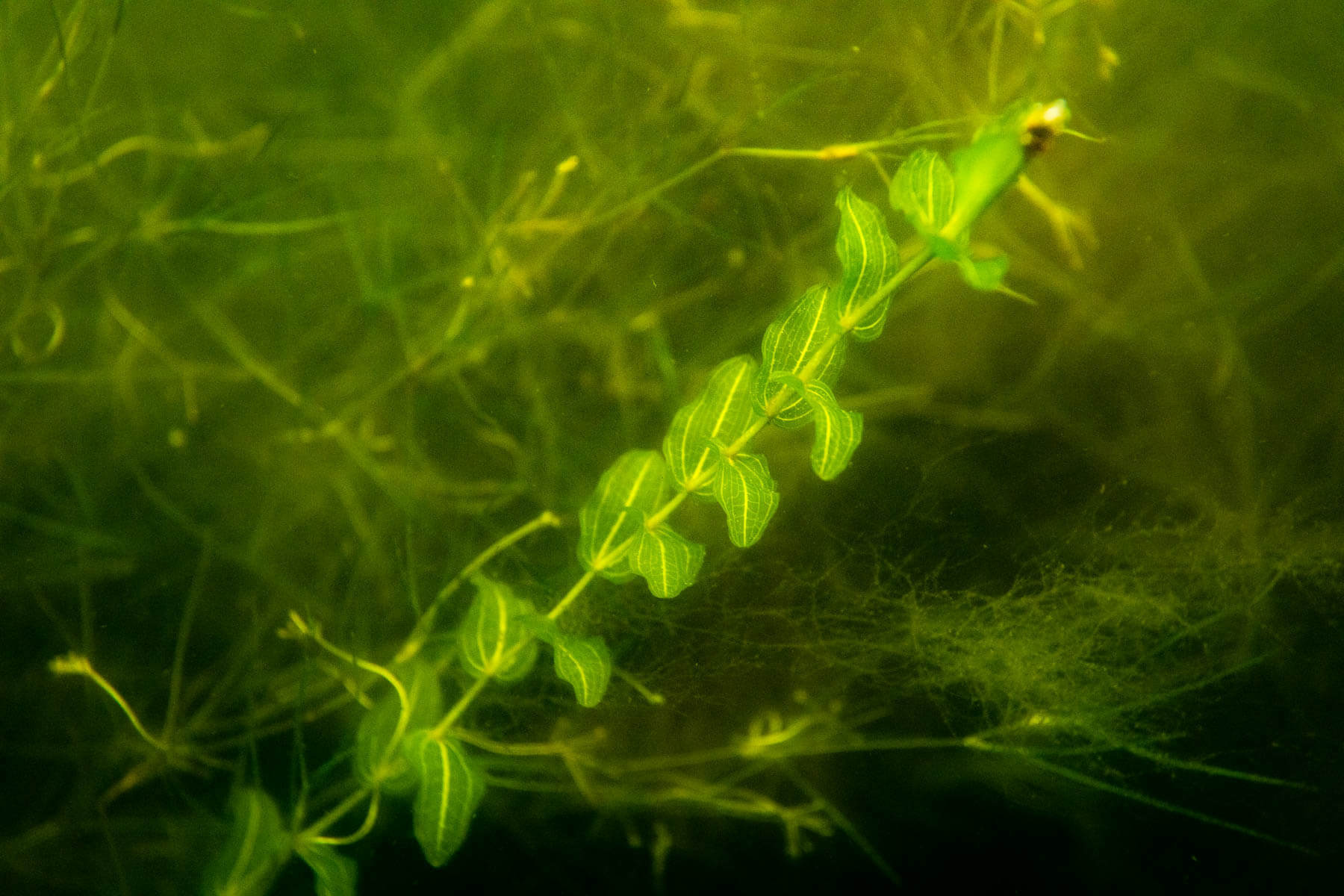

Quietly present in our fields and neighborhoods, winding through our towns and cutting through the woods, are the thousands of rivers and streams of the Chesapeake watershed that make their way to the Bay. From above those waters can all look the same, but a whole world of plants we call “underwater grasses” exists below the surface. In a landmark study funded in part by the National Science Foundation and published earlier this year in the journal of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, Chesapeake researchers from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science and colleagues from universities across the country found that the many different varieties of grasses growing in the water—from our rivers and streams to the bay—are critical in helping our ecosystems to endure changes.

Biodiversity is important for large-scale resilience

The researchers studied multiple populations, from underwater grasses of the Chesapeake to beetles of the Sonoran Desert, to get a look at the importance of biodiversity on more than one regional scale. Their results found that environmental homogenization (having only the same few species in a given area) represents an emerging threat because it increases the likelihood of intense fluctuations for the wider ecosystem. Changes that occur to a species in one area will likely occur to other pockets of that same species in nearby areas in similar ways (a phenomenon known as the Moran effect).

It can sound confusing, but what it really means is that having the same few species makes the whole environment less resilient in the face of change.

“Having low biodiversity is like putting all your eggs in one basket and puts us at greater risk of something catastrophic happening,” explained lead study author Dr. Christopher Patrick. “We’ve known this for a long time, but never before have we shown this to be true for entire regions and landscapes.”

Any change can cause disruption, and the Chesapeake region is no exception. In 2018, record rainfall fell across the majority of the watershed, smashing records in several cities and states but also dramatically impacting the Bay’s grass beds and overall water quality. Only the year before, grass beds showed record acreage and the healthiest water in decades. All the 2018 rain increased the amount of freshwater that flowed into the Bay—in fact, the U.S. Geological Survey recorded it as the highest flow levels ever experienced in this region. 2019 then brought drought conditions and a polar vortex, leading to a significant decline in both grass bed acreage and water quality.

Change is unavoidable and life in the water can be unpredictable, but having a biodiversity of plants means any one grass bed can better absorb and bounce back from the impacts.

Benefits of underwater grasses

Underwater grasses (also called “submerged aquatic vegetation” or SAV) form beds in the Bay and its tidal tributaries that act like aquatic forests. Crustaceans and worms burrow in the sediment while fish, crabs and other creatures hide, feed and reproduce in the shelter of the waving grasses. Many Chesapeake species, including the famous blue crab, rely on the underwater grass beds as nurseries for their young.

Like forests on land, underwater grass beds absorb carbon dioxide and provide oxygen. Underwater grasses are so efficient at this absorption that they are referred to as a carbon sponge, and their presence can even counteract acidification.

The individual plant parts of underwater grasses are also perfectly designed to absorb nutrients, which are a source of many of the Chesapeake watershed’s problems. Excess nutrients from fertilizers and other land activities can cause algae to bloom, leading to the formation of dead zones as the algae die off and decompose. In an underwater grass, the rhizome (which anchors a plant to the bed), the roots, and the blades (the “leaves” of the underwater grasses) all soak up nutrients, making underwater grasses nutrient absorption powerhouses!

As valuable as underwater grasses are, how widespread they are in the Bay and its tributaries can vary from year to year. Let’s say a grass bed contains only one species, and that species experiences a bad year. Just like that, the Bay’s overall underwater grass numbers can plummet. This happened in 2019, when widgeon grass performed poorly and entire beds of it disappeared in the Bay. In rivers that contained more than one species, beds were able to persist in the face of the widgeon grass loss.

Underwater grasses of the Chesapeake watershed

We’re lucky enough to have several species of underwater grasses that naturally make their home in the Bay and its tidal tributaries. As you move from the fresh, low-salt rivers at the top of the watershed down to the salty waves of the open Bay, you will find different species of underwater grasses in the fresh, brackish and salty habitats. Salinity levels, measured in parts per thousand (ppt), differentiate the different habitats.

Fresh water – tidal fresh (<0.5 ppt) and oligohaline ( 0.5-5 ppt)

The low-salt areas of the Bay and its tributaries generally support the same underwater grass species, of which there are more than a dozen in the Chesapeake. Some of these freshwater species include wild celery, curly pondweed, water stargrass, coontail, Canadian waterweed (Elodea canadensis), and slender pondweed as well as multiple Naiad species and other pondweeds.

The variety of freshwater species can be particularly enchanting: In summer, star grass puts up beautiful small, yellow, six-petaled flowers above the water’s surface. Coontail, vibrantly green and pleasingly fern-like, holds its shape out of the water and is named for its resemblance to a raccoon’s tail.

Slightly brackish water – mesohaline (5-18 ppt)

As you move further into the Bay, you begin to find brackish water. Some underwater grass species can live at various salinity ranges but do best in a brackish habitat. Welcome to the mesohaline, where redhead grass, sago pondweed and horned pondweed tend to thrive. Horned pondweed, which can tolerate both lower and higher salt ranges, is also an early arriver. It is usually the first species to appear in spring.

Brackish to salty water - polyhaline (18-30 ppt)

As you move down the Bay and closer to the Atlantic Ocean, you come into the saltiest water—the polyhaline—which supports two underwater grass species. Eelgrass, a robust-bladed species, prefers the increased salt content but is intolerant of high heat. Widgeon grass, abundant but variable and thin-bladed, tolerates this salty habitat and produces a fruit which provides food for fish and birds. Even having a mix of just these two species in our Bay waters can provide more resilience than a bed that contains a single species.

Most people think of underwater grasses like the grass of a lawn—unchanging, unremarkable—but a closer look reveals a whole world of unique characteristics and fascinating features that are interesting for humans and crucial for an ecosystem.

The Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment study showed that biodiversity, whether on land or under the water, leads to more resilient and healthier habitats. How we manage natural spaces for biodiversity in the years to come will play a large role in whether our habitats are ready to face whatever changes the future may hold.

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories